Excessive drinking can damage the liver. Yet, unlike obesity or high cholesterol, clinicians only screen for alcohol use by asking their patients how much they drink.

Turns out that method is not always reliable, and a blood test can help determine whether a person’s drinking may be causing liver disease.

Researchers at UC San Francisco say it would be a more reliable way to assess a person’s drinking, so clinicians can intervene in time to prevent more serious damage.

We don’t ask someone how much fatty food they eat. We measure their cholesterol. We don’t ask people how much they think they weigh. We weigh them.”

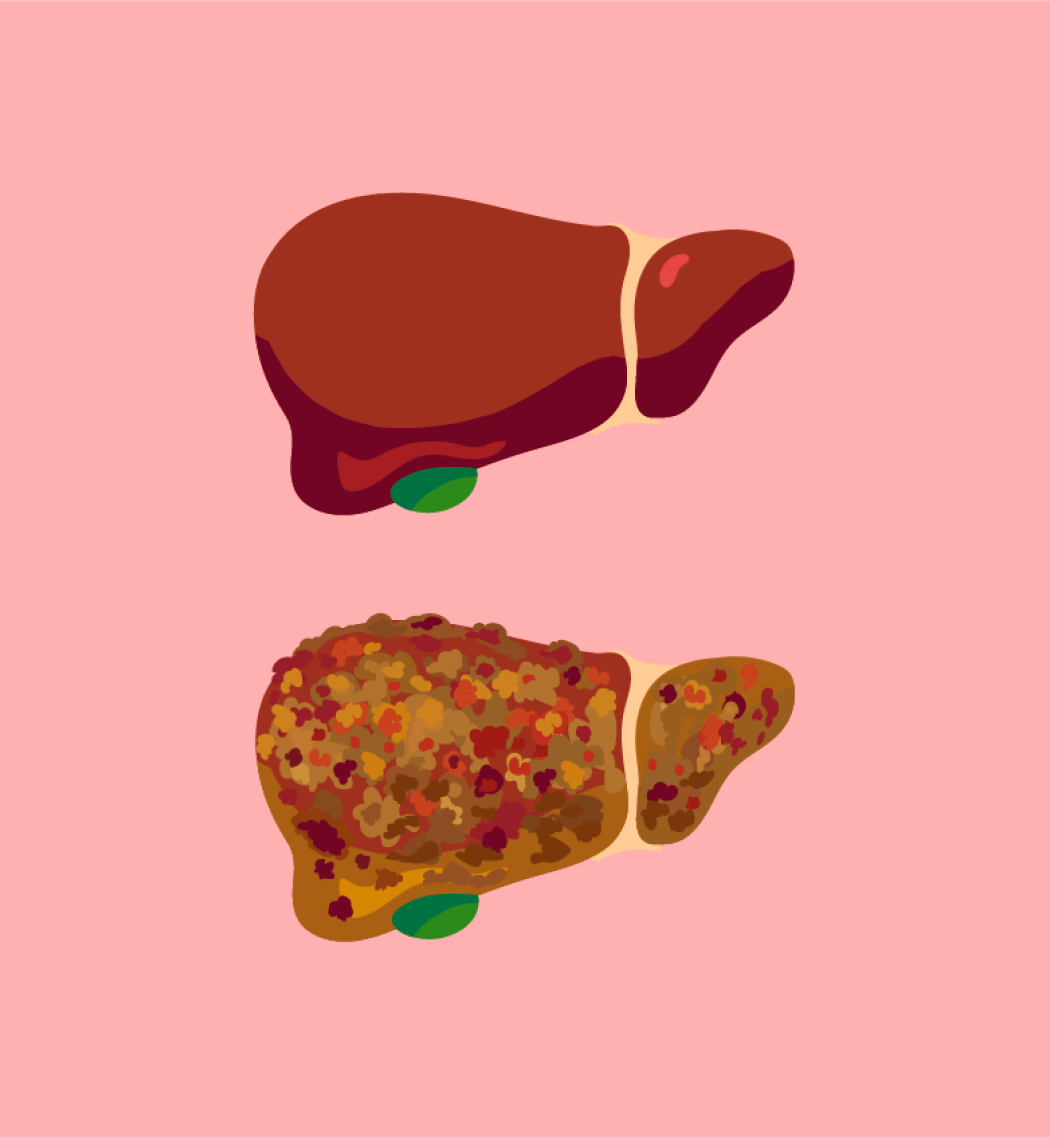

By using a biomarker called phosphatidylethanol, or PEth for short, clinicians could gain a clearer picture of risk for liver fibrosis, which is a buildup of scar tissue in the liver.

The condition can be treated if it is caught early. Without treatment, it can lead to cirrhosis, liver failure and liver cancer.

“This is a more direct way to measure the harm that alcohol is causing in the body than asking patients,” said Judy Hahn, PhD, a professor in the Division of HIV, Infectious Diseases and Global Medicine at UCSF. “We don’t ask someone how much fatty food they eat. We measure their cholesterol. We don’t ask people how much they think they weigh. We weigh them.”

The study appears in the American Journal of Gastroenterology.

How the biomarker measures alcohol use

The researchers compared two indicators of alcohol use – PEth and self reports – to see how well they correlated with Fibrosis 4, or FIB-4 for short, which is an indicator of liver disease risk.

While PEth is measured directly in the blood, FIB-4 is a composite score based on a person’s age and the results from several other blood tests.

They found that PEth closely tracked FIB-4 – but the correlation between self-reported drinking and FIB-4 was much weaker. This could be because the people in the studies either minimized or could not remember how much alcohol they had consumed.

The study, which included more than 4,000 people in the United States, Russia, Uganda and South Africa, is the largest examination yet of the association between PEth and liver fibrosis risk. And it is the first to compare PEth with self-reported alcohol use in terms of how well each one indicates the risk of fibrosis.

Liver fibrosis can be slowed or even reversed by limiting the consumption of alcohol and improving one’s diet – for example by reducing sugar, fat and salt. And it is critical to catch the disease before it progresses to the more severe stages of liver disease.

In the future, the authors said, PEth screening could be included with other routine blood tests, like those for cholesterol and blood sugar.

“To prevent and manage liver fibrosis, we need to know how much a person is drinking,” said Pamela Murnane, PhD, MPH, an assistant professor of epidemiology and biostatistics and the first author of the study. “We clearly don’t have a good grasp on that with self-report.”

Authors: Additional UCSF co-authors include Gabriel Chamie, MD, Mandana Khalili, MD, and Phyllis C. Tien, MD.

Funding: The study was funded with a grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIAAA K24 AA022586).