How This Cancer Drug Could Make Radiation a Slam Dunk Therapy

UCSF scientists combine a precision drug therapy with an antibody and radiation to eliminate tumors without causing side effects.

Radiation is one of the most effective ways to kill a tumor. But these therapies are indiscriminate, and they can damage healthy tissues.

Now, UC San Francisco scientists have developed a way to deliver radiation just to cancerous cells. The therapy combines a drug to mark the cancer cells for destruction and a radioactive antibody to kill them.

It wiped out bladder and lung tumors in mice without causing lethargy or weight loss – the typical side effects of radiation therapy.

“This is a one-two punch,” said Charly Craik, PhD, a professor of pharmaceutical chemistry at UCSF and co-senior author of the study, which appears Dec. 10 in Cancer Research. “We could potentially kill the tumors before they can develop resistance.”

A cancer drug becomes a molecular flag for cancer

The project began 10 years ago when UCSF’s Kevan Shokat, PhD, discovered how to attack KRAS, a notorious cancer-causing protein. When mutated, KRAS spurs out-of-control cell growth. Such mutations lead to up to a third of all cancer.

Unlike external beam radiation, this method uses only the amount of radiation needed to beat the cancer.”

Shokat’s breakthrough led to the development of drugs that latched onto cancerous KRAS. But the drugs could only shrink tumors for a few months before the cancer came roaring back.

The drugs stayed bound to KRAS, however, and Craik, wondered whether they might make cancer cells more “visible” to the immune system.

“We suspected early on that the KRAS drugs might serve as permanent flags for cancer cells,” Craik said.

In 2022, a UCSF team that included Craik and Shokat demonstrated this was indeed possible.

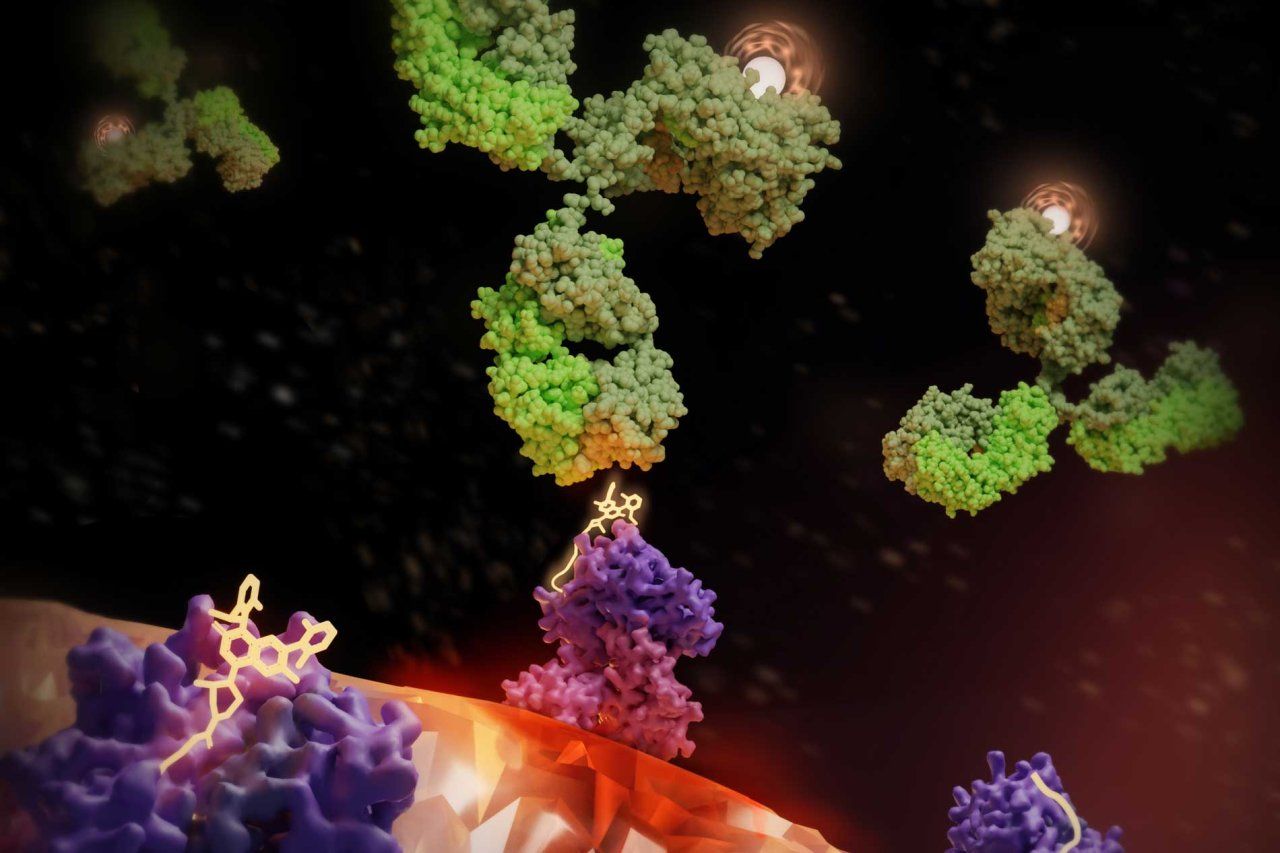

The team designed an antibody that recognized the unique drug/KRAS surface fragment and beckoned to immune cells.

But the approach needed the immune system to have the strength to beat the cancer by itself, which turned out not to be that effective.

Bringing atomic-level radiation to cancer cells

Around the same time, Craik began working with Mike Evans, PhD, a professor of radiology at UCSF, to develop a different approach to destroy cancer cells.

They still used the K-RAS drug to flag cancerous cells, but this time they armed the antibodies with radioactive payloads.

The combination worked, eliminating lung cancer in mice with minimal side effects.

“Radiation is ruthlessly efficient in its ability to ablate cancer cells, and with this approach, we’ve shown that we can direct it exclusively to those cancers,” Evans said.

Added Craik, “The beauty of this approach is that we can calculate an extremely safe dose of radiation. Unlike external beam radiation, this method uses only the amount of radiation needed to beat the cancer.”

A radiation therapy for all patients

To make this therapy work in most patients, scientists will have to develop antibodies that account for the different ways that people’s cells display KRAS.

The UCSF team is now working on this – motivated by their own evidence that it can work.

Kliment Verba, PhD, an assistant professor of cellular and molecular pharmacology at UCSF, used cryo-electron microscopy to visualize the ‘radiation sandwich’ in atomic detail, giving the field a structure to develop even better antibodies.

“The drug bound to the KRAS peptide sticks out like a sore thumb, which the antibody then grabs,” said Verba, who like Craik is a member of UCSF’s Quantitative Biosciences Institute (QBI). “We’ve taken a significant step toward patient-specific radiation therapies, which could lead to a new paradigm for treatment.”

Authors: In addition to Craik, Evans, and Verba, other UCSF authors are Apurva Pandey, PhD, Peter J. Rohweder, PhD, Lieza M. Chan, Chayanid Ongpipattanakul, PhD, Dong hee Chung, PhD, Bryce Paolella, Fiona M. Quimby, Ngoc Nguyen, MS.

Funding and disclosures: This work was supported by the NIH (T32 GM 064337, P41-GM103393, S10OD020054, S10OD021741, and S10OD026881), the UCSF Innovation Ventures Philanthropy Fund, the UCSF Marcus Program in Precision Medicine, and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Craik, Evans, and Rohweder are inventors on a patent application covering part of this work and owned by UCSF. Craik, Ongpipattanakul, and Rohweder are inventors on a patent application related to this technology owned by UCSF. Craik and Rohweder are co-founders and shareholders of Hap10Bio and Evans and Paolella are shareholders of Hap10Bio.