Scientists have long suspected the keto diet might be able to calm an overactive immune system and help some people with diseases like multiple sclerosis.

Now, they have reason to believe it could be true.

Researchers at UC San Francisco have discovered that the diet makes the gut and its microbes produce two factors that attenuated symptoms of MS in mice.

If the study translates to humans, it points toward a new way of treating MS and other autoimmune disorders with supplements.

The keto diet severely restricts carbohydrate-rich foods like bread, pasta, fruit and sugar, but allows unlimited fat consumption.

Without carbohydrates to use as fuel, the body breaks down fat instead, producing compounds called ketone bodies. Ketone bodies provide energy for cells to burn and can also change the immune system.

Working with a mouse model of MS, the researchers found that mice who produced more of a particular ketone body, called β-hydroxybutyrate (βHB), had less severe disease.

The additional βHB also prompted the gut bacterium Lactobacillus murinus to produce a metabolite called indole lactic acid (ILA). This blocked the activation of T helper 17 immune cells, which are involved in MS and other autoimmune disorders.

“What was really exciting was finding that we could protect these mice from inflammatory disease just by putting them on a diet that we supplemented with these compounds,” said Peter Turnbaugh, PhD, of the Benioff Center for Microbiome Medicine.

Earlier, Turnbaugh had shown that when secreted by the gut, βHB counteracts immune activation. This prompted a postdoctoral scholar who was then working in his lab, Margaret Alexander, PhD, to see if the compound could ease the symptoms of MS in mice.

In the new study, which appears Nov. 4 in Cell Reports, the team looked at how the ketone-body-rich diet affected mice that were unable to produce βHB in their intestines, and found that their inflammation was more severe.

But when the researchers supplemented the diets with βHB, the mice got better.

To find out how βHB affects the gut microbiome, the team isolated bacteria from three groups of mice that were fed either the keto diet, a high-fat diet, or the βHB supplemented high-fat diet.

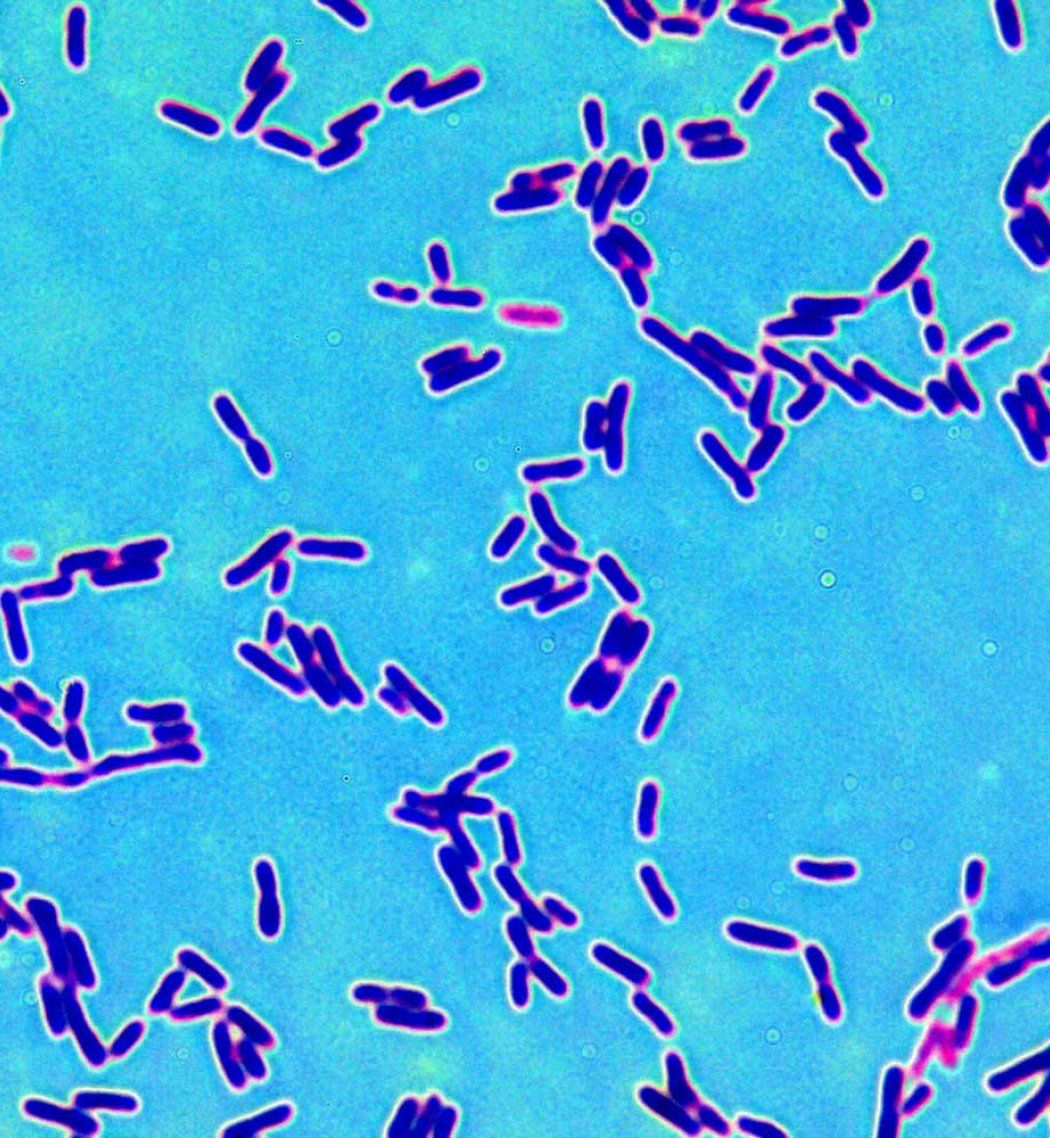

Then, they screened the metabolic products of each group’s distinct microbes in an immune assay and determined that the positive effects of the diet were coming from a member of the Lactobacillus genus: L. murinus.

Two other techniques, genome sequencing and mass spectrometry, confirmed that the L. murinus they found produced indole lactic acid, which is known to affect the immune system.

Finally, the researchers treated the MS mice with either ILA or L. murinus, and their symptoms improved.

Turnbaugh cautioned that the supplement approach still needs to be tested in people with autoimmune disorders.

“The big question now is how much of this will translate into actual patients,” he said. “But I think these results provide hope for the development of a more tolerable alternative to helping those people than asking them stick to a challenging and restrictive diet.”

Authors: In addition to Turnbaugh and Alexander, authors include Vaibhav Upadhyay, Rachel Rock, Lorenzo Ramirez, Kai Trepka, Diego Oreilana, Qi Yan Ang, Caroline Whitty, Jessie Turnbaugh, Darren Dumlao, Renuka Nayak, and John C. Newman of UCSF, Patrycja Puchalska and Peter Crawford of the University of Minnesota, and Yuan Tian and Andrew Patterson Pennsylvania State University.

Funding: This work was funded by the NIH (grants P30 DK063720, R01DK114034, R01HL122593, R01AR074500, R01AT011117, F32AI14745601, K99AI159227, R00AI159227-03, K08HL165106, K08AR073930, R01AG067333, R01DK091538, R01AG069781) and the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation (DRR4216). Turnbaugh is a Chan Zuckerberg Biohub-San Francisco Investigator.