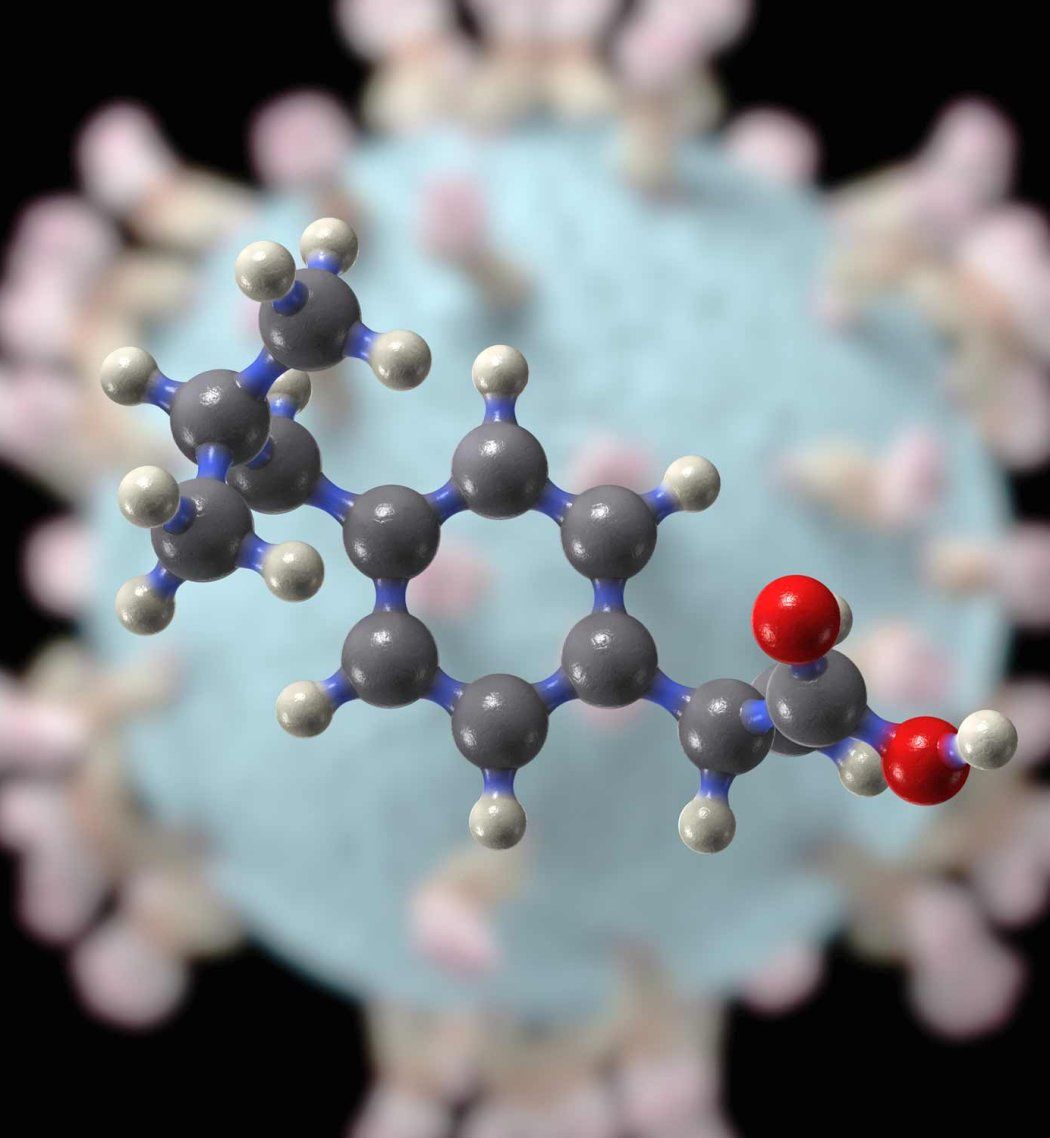

Small molecules like gabapentin, metformin and ibuprofen are still the mainstay of the pharmaceutical trade because they are easy to make and distribute and can get around the body.

But they also have a downside: Once inside cells, small molecules may act in unintended ways, causing dangerous side effects.

Now, researchers are using artificial intelligence (AI) to map the terrain of these “off” or unwanted targets. They hope the map will speed up drug development and lower the costs by avoiding problems that may only become apparent late in the development process.

James Fraser, PhD, who chairs the Department of Bioengineering and Therapeutic Sciences in the UCSF Schools of Pharmacy and Medicine, is leading a multidisciplinary team that will receive up to $30 million in federal funding to identify what he calls “anti-targets,” the sites on proteins that drugs should avoid. In the last 40 years, scientists have learned that most of these sites are found on a relatively small subset of all the proteins the body produces.

The team will use the catalog of anti-targets to train a machine-learning model to predict how molecules will interact with them. That predictive power will allow researchers to alter and refine potential therapeutic molecules before ever manufacturing the drug and testing it in animals or humans.

“This is the first time anyone has taken this kind of counterintuitive approach,” said Fraser, noting that drug developers, logically, pursue protein targets that will produce positive effects.

“But there’s an almost infinite number of molecules we can test as drugs,” he said. “So, it makes sense for us to define rules around when things may go wrong if a molecule also engages these anti-target proteins, and then work around those.”

The funding, from the Advanced Research Projects Agency for Health (ARPA-H) initiative, supports breakthrough research efforts with the potential to improve health outcomes.

The award covers a multidisciplinary team across four entities, bringing a broad range of expertise to the effort.

Fraser and others at UCSF will focus on detailing the specific structures of the molecules as they interact with different proteins. The nonprofit Open Molecular Software Foundation, along with John Chodera, PhD, a computational chemist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, will create the open-source AI models and guide decisions on which molecules to test. Biotech company Octant, based in the Bay Area, will produce and test prospective molecules.

The partnership is called the OpenADMET Consortium. A catchall term for problems that must be navigated in the drug discovery process, ADMET stands for absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, toxicity.

The project will be augmented by data from two of NIH’s Antiviral Drug Discovery (AViDD) Centers for Pathogens of Pandemic Concern: one under the QBI Coronavirus Research Group at UCSF’s Quantitative Biosciences Institute (QBI) led by Nevan Krogan, PhD; the other at the AI-Driven Structure-Enabled Antiviral Platform (ASAP) Discovery Consortium.

Fraser said that having AI do the refinement work on the front end will significantly speed up drug development, and he expects to see progress very soon.

“This is a problem we can solve,” he said. “Once we have these open-source datasets and models, every biotech company will be able to use them and, hopefully, be motivated to contribute their data to improve them. It will really revolutionize the way we create new drugs.”