When dentists look inside your mouth, they’re not just looking for cavities. They’re looking for gum disease and oral cancers, as well as assessing the overall health of the millions of bacteria, fungi and viruses that live there – mostly, but not always, harmoniously.

“For a long time, people assumed that oral health is about brushing your teeth, aesthetics and bad breath. But the mouth is the main entry point between the outside world and the inside of your body,” said Margôt Bacino, a graduate student researcher in the oral craniofacial sciences program at UCSF’s School of Dentistry. “We need to understand how the oral microbiome functions and how it influences our overall health, since there are links between oral health and many inflammation-related conditions, including Alzheimer’s disease, rheumatoid arthritis, obesity, diabetes and adverse pregnancy outcomes.”

Those millions of bacteria, fungi and viruses interacting in your mouth are what health care providers call the oral microbiome. Bacino is one of many researchers and clinicians in the School of Dentistry studying it so they can develop new treatments and prevent diseases. The oral microbiome is the second most diverse in the human body, after the gut, yet relatively understudied – which is why researchers believe it holds great potential for advancements in health.

“Many of health’s mysteries are waiting to be solved through the study of oral microbiota,” said Michael Reddy, DMD, DMSc, dean of the School of Dentistry and associate vice chancellor, Oral Health Affairs. “UCSF is investing in this domain of research because it holds so much promise for early detection of serious diseases – not just in the mouth but using the oral microbiome as an indicator of health throughout the body. The links between conditions in the mouth and overall health require that we think more holistically than we have been, not only in terms of research but also care delivery. This is why dentists at UCSF use the same health record as our colleagues in medicine, nursing, and pharmacy, and we’re working together to deliver whole-person health care.”

That’s also why microbiome research is multidisciplinary at UCSF. The Benioff Center for Microbiome Medicine (BCMM) at UCSF is a centralized home for human microbiome research across UCSF’s four schools, Medicine, Dentistry, Pharmacy and Nursing. It supports research like Bacino’s, as well as others studying microbiomes of the gut, skin, respiratory system and more – along with efforts to diversify the microbiome workforce and symposia. BCMM launched five years ago thanks to Marc and Lynne Benioff, and the oral microbiome research program began three years ago with a gift from Larry Berkelheimer and is expanding its research facilities at the Parnassus Heights campus with an $8 million federal award it recently received.

“At the BCMM, we’ve moved toward integrative, multidisciplinary research, with the increasing appreciation for the role of the oral microbiome in both oral and systemic health,” said Sue Lynch, PhD, professor in the School of Medicine and director of the BCMM. “In addition to inflammatory disease treatment, we’re also firmly focused on prevention. There are so many chronic diseases with no cure, we want to develop microbial-derived strategies for both managing and preventing these conditions.”

In her family’s footsteps

Because of its prevalence, lack of treatments and impact on the health of other organs, a central focus of oral microbiome research is periodontitis, a serious gum infection that damages the soft tissue around teeth. About 40% of U.S. adults over 30 years old have some level of periodontitis, which can be caused by factors such as poor oral hygiene, smoking, pregnancy and family history. That number climbs to 60% for adults over 65, according to the Center for Disease Control (CDC).

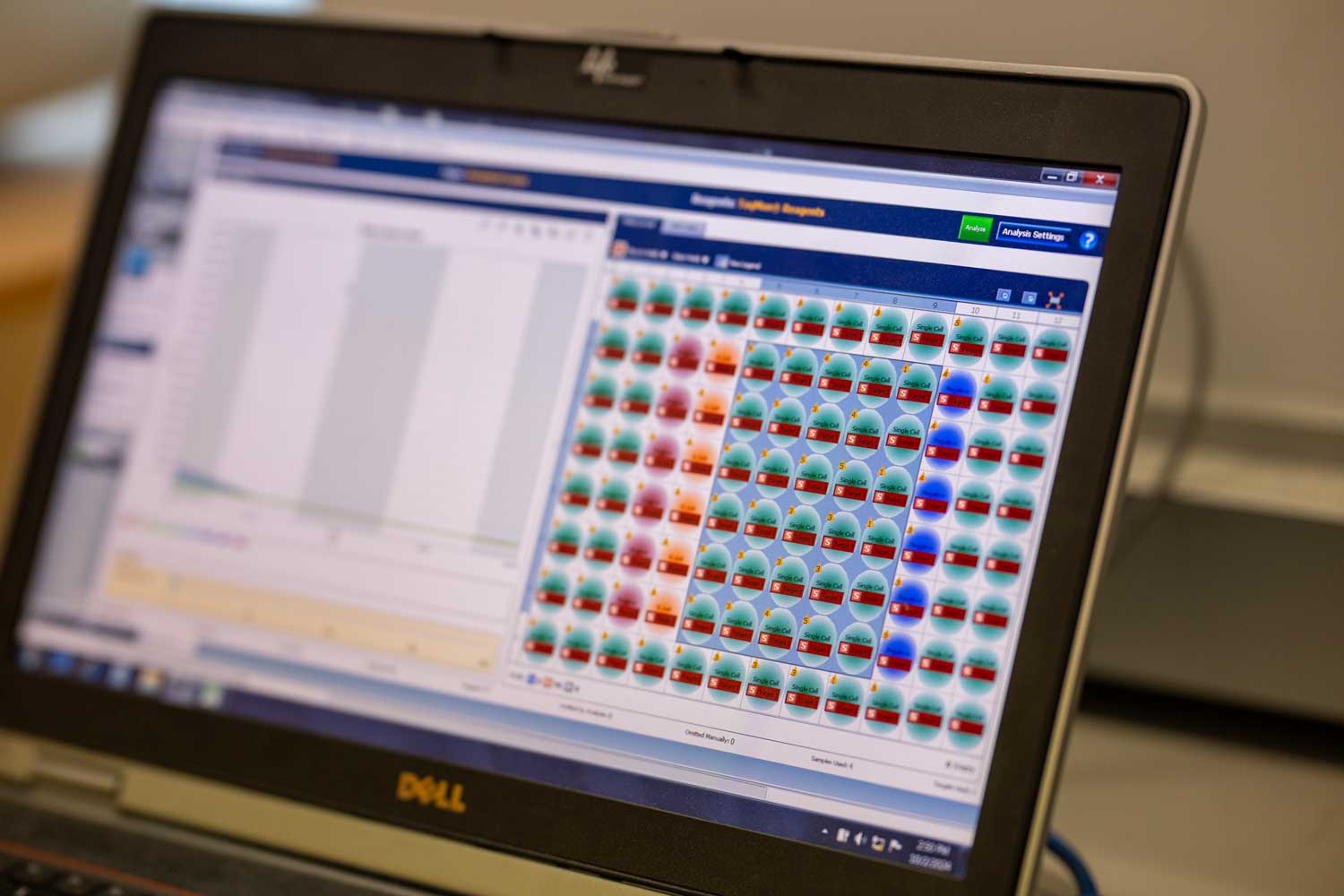

As a member of Lynch’s lab, Bacino creates clones of E. coli bacteria that have DNA from the oral microbiome added to them. She has screened thousands to see if they can inhibit oral bacteria that are associated with periodontal disease.

“Right now, current treatments for periodontal disease rely on repeated deep cleaning often paired with antibiotics. My ultimate goal is to expand clinicians’ tool sets to better treat periodontal disease,” said Bacino, who follows in the footsteps of her grandfather, an aunt and an uncle who are dentists. “I’m looking for certain microbes that inhibit others associated with periodontal disease, the ones that influence how the whole microbiome acts and wreak havoc on someone’s oral health. It’s like when there’s one rambunctious kid in a class, they make the whole class behave differently. I’m looking for ways to keep the class calm without removing that one kid – and I’m finding a few possibilities that I’m starting to research more.”

Once Bacino identifies the microbes and specific genes that can slow their growth, she wants to turn that into a treatment. “I believe it’s possible to harness aspects of a healthy person’s mouth and translate that into new treatments,” she said. “Depending on the microbe, maybe it could be a new probiotic that a patient takes or a new concentrated mouthwash.”

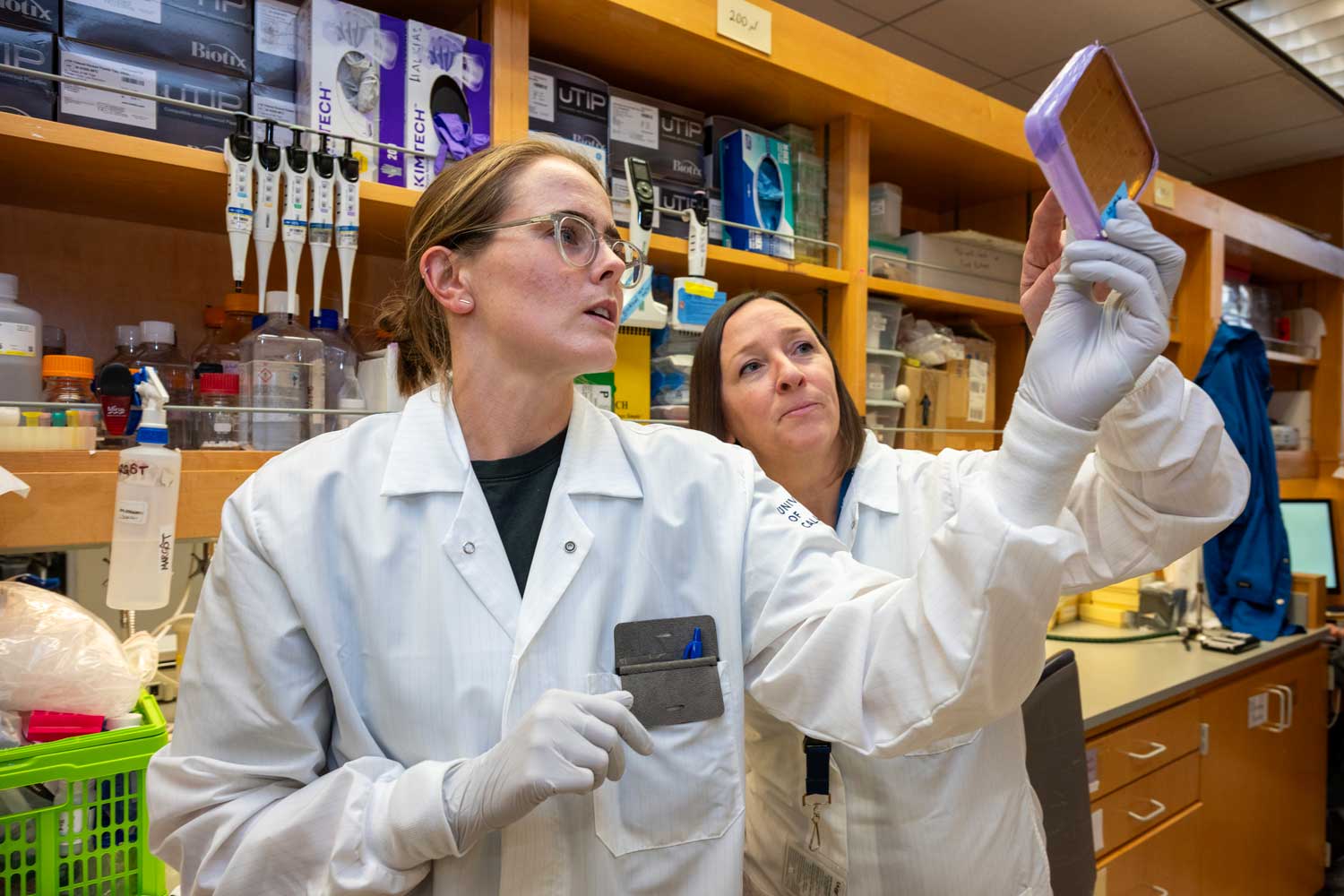

Bacino partners with UCSF dentists and dental students to collect her samples. “It’s beneficial that at UCSF we have both patient clinics and research labs at the same campus. The moment samples are taken from a human mouth, they begin to change for the worse – RNA degrades, microbes die. I work with our clinicians to collect samples in a way that keeps the cells as fresh as possible, and then it’s just a short 10-minute walk between the collection site and the lab, so I have a lot of control over the samples.”

Does periodontitis contribute to preterm births?

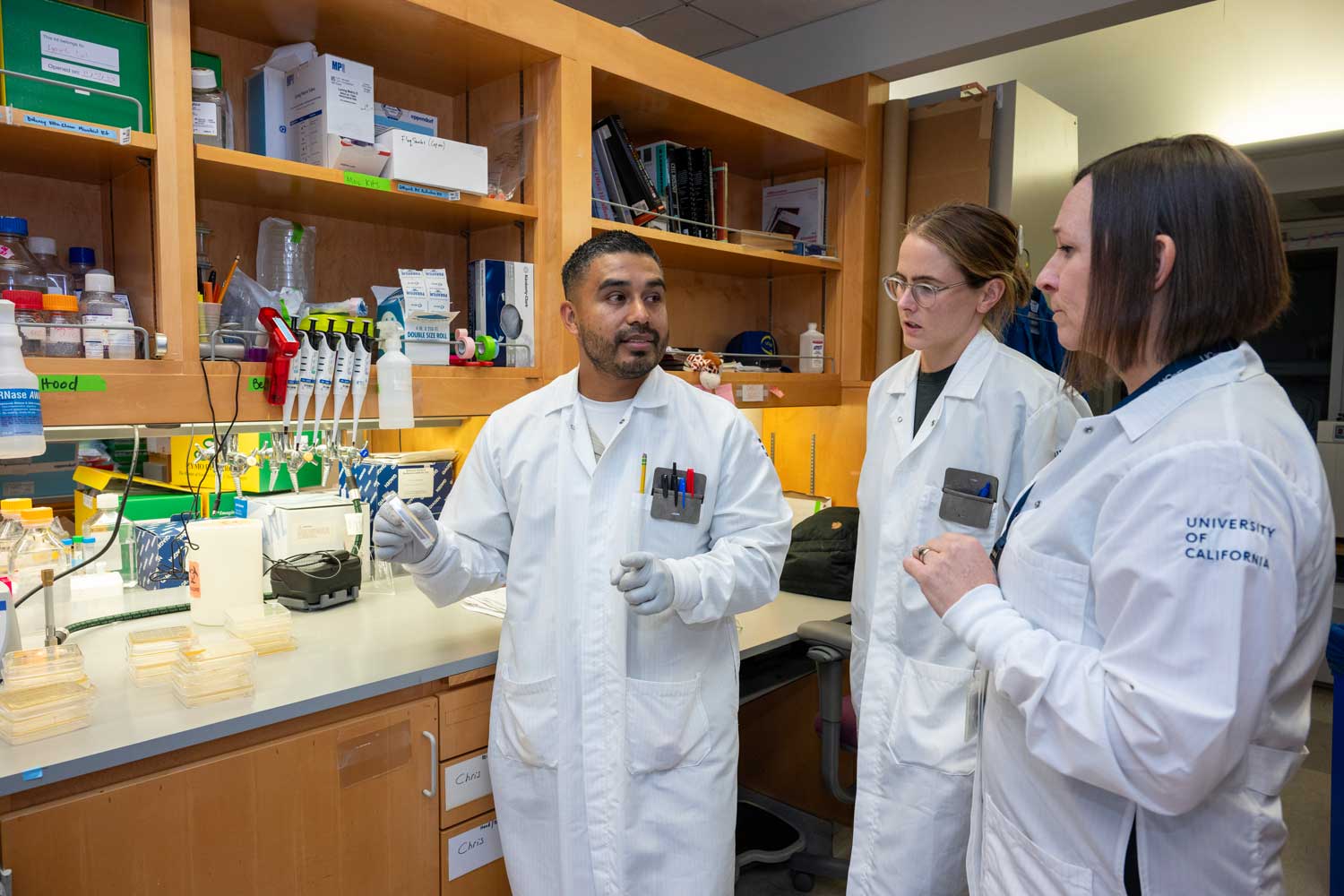

Christopher Bravo’s research takes a different approach to periodontitis, investigating how the oral microbiome is associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes like preterm birth.

“We know there is an oral-uterine connection, and we need to understand it more, especially since it disproportionately impacts minority patients,” said Bravo, also a graduate student in the oral craniofacial sciences program at UCSF’s School of Dentistry and part of Lynch’s lab.

His research looks at oral bacteria that are prevalent in the early stages of infant life from the womb to the first several weeks of life, specifically in babies born preterm or whose mothers suffered from adverse pregnancy outcomes. Approximately 40% of pregnant women have some form of periodontal disease, and although researchers don’t yet know why, that rate is higher among racial and ethnic minorities and women of low socioeconomic status, according to the National Institute of Health. About 10% of babies in the U.S. are born preterm, before 37 weeks, and they can face a host of health issues from breathing and vision difficulties to jaundice and an increased susceptibility for infection. Black women are twice as likely to have a preterm birth than white women, according to the CDC.

To identify pathogens that might contribute to preterm birth, Bravo studies microbes in both mothers and newborn preterm babies, analyzing the data to find where microbes overlap between mother and baby.

“Our goal is to understand how oral microbes can manipulate the immune system to evade maternal and fetal immune responses because that’s when health issues can take root before a baby is born,” said Bravo. “With this knowledge, we can uncover the mechanisms that contribute to adverse pregnancy outcomes that affect both mothers and infants, and set up more babies with healthy foundations for healthier futures.”

A special advantage

There are more than 120 faculty, staff and trainees in all four UCSF schools working on microbiome research projects with a shared goal of learning as much as possible about the human microbiome. Dentistry learners like Bacino and Bravo appreciate how the interactions they have advance their oral microbiome research faster.

“Within the Lynch lab, we all share the commonality of studying microbes, but we work on different aspects,” Bacino said. “The lab is full of different perspectives that we offer to each other. We’re starting to see connections between different parts of the body, from head to toe, and that’s a wonderful environment to study in.”

Bravo said being a Dentistry student working under the umbrella of BCMM affords him helpful opportunities for collaboration, guidance and mentorship. “I like working in the context of different fields and approaches. I have a lot of flexibility in how I study and explore the oral microbiome.”

Lynch said the partnership between the clinicians and researchers in the Schools of Dentistry and Medicine gives UCSF a special advantage when it comes to oral microbiome discoveries.

“Collaboration is in our DNA at UCSF, and it’s truly what drives us. We collaborate across disciplines and focus on research that’s tailored to specific issues people face. It’s the future of accelerated discovery and our research efforts in human health,” she said. “The oral microbiome is relatively understudied and requires new tools to investigate it. We have developed these new tools, which are allowing us to examine oral microbiomes in unprecedented ways. These advantages are critical to the development of new treatments and disease prevention strategies.”