The cornerstone of any building is essential to its success.

It needs to be sturdy, able to carry a large load and symbolic of the growth to come.

That holds especially true for the laying of the cornerstone for the very first medical building at UC San Francisco’s historic Parnassus Heights campus, an occasion set in motion by a politician’s generous donation, the appetite for a University of California medical school and unpopular sand dunes on the edge of late 1800s San Francisco.

But if public opinion had swayed its location, UCSF may not exist as it does today.

‘The falling tears of Aesculapius’

While the day was momentous, the stone of the inaugural medical building was laid in less than ideal conditions.

On March 27, 1897, the weather was “rain and blowing sand.”

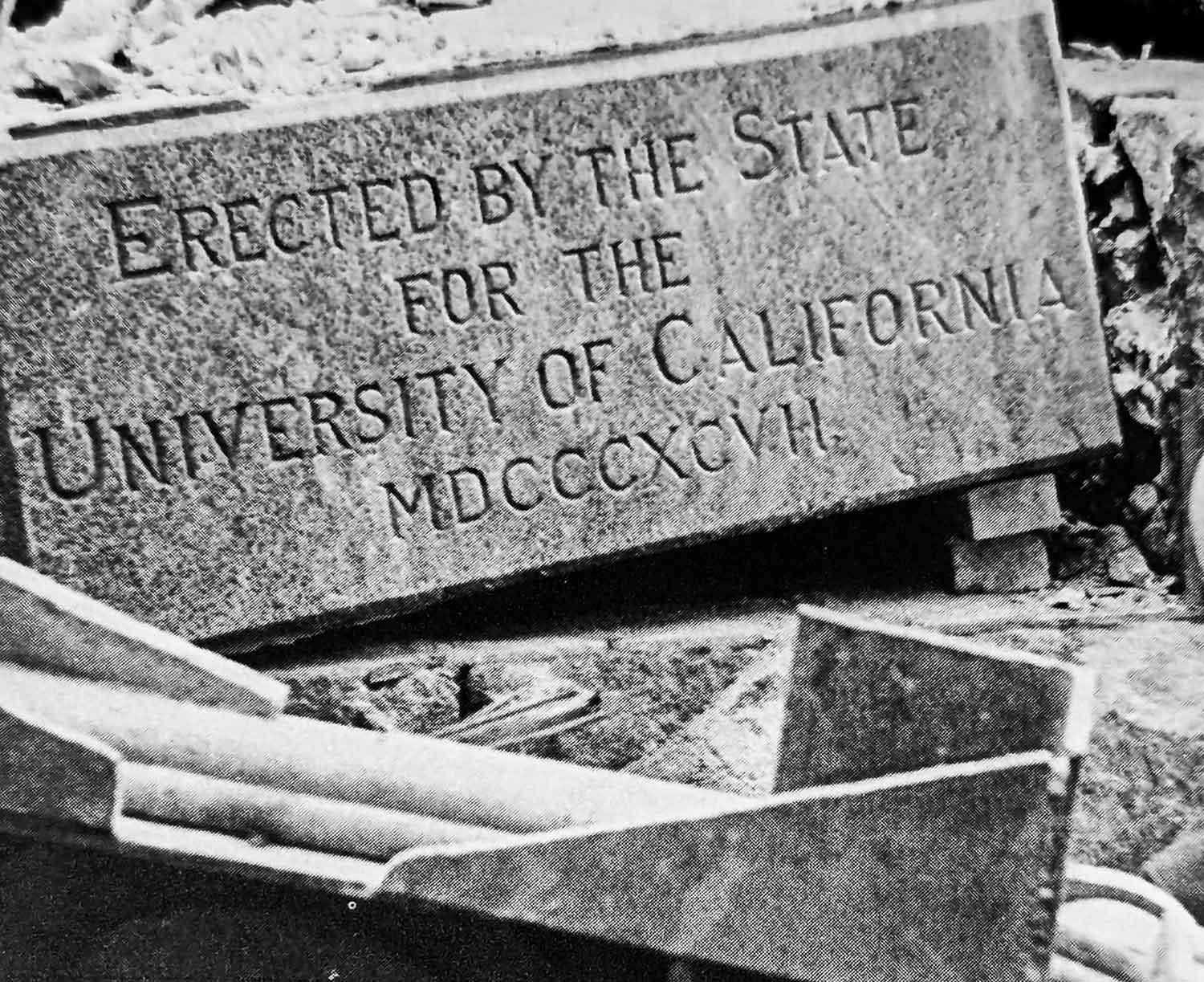

It was a day that brought dignitaries, politicians and leaders of the new medical school to what was then known as Mount Parnassus, a soggy scene described in “The University of California: A Pictorial History.” The inscription on the cornerstone’s granite read simply: “Erected by the State for the University of California MDCCCXCVII.”

Those Roman numerals translate to 1897.

At the celebration, California Lieutenant Governor William Jeter summed it up best: “Spread out before us, we behold as beautiful and lovely a landscape as one could imagine. At our very feet, Golden Gate Park with its green lawns, rising trees, and winding paths, while strains of music float softly through the air.”

The opening celebration, 1897

A photo of the 1897 groundbreaking of the first medical building at what is now known as the UCSF Parnassus Heights campus.

The cornerstone of the inaugural medical building, which reads “Erected by the State for the University of California MDCCCXCVII (1897).”

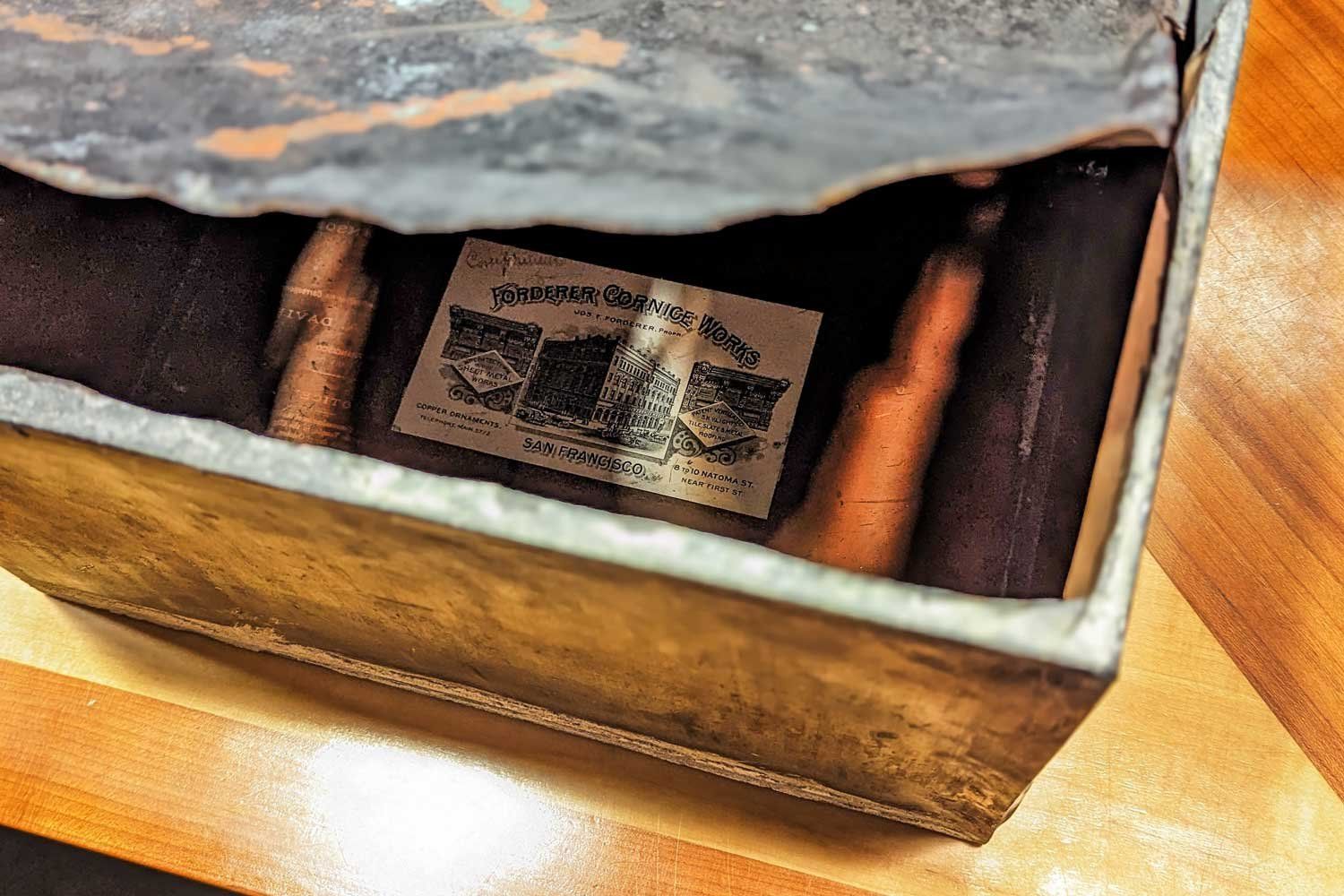

Inside the cornerstone was a specially made copper box built as a time capsule by Forderer Cornice Works on Natoma Street in San Francisco.

Its contents were well preserved for decades until UCSF officials opened it again precisely 70 years and two months later when the same building was demolished to make way for newer, more modern facilities. Items included copies of San Francisco’s six, yes six, daily newspapers from March 26-27, 1897, the oldest photograph of what eventually became the original Parnassus Heights campus site, a copy of the California State Legislature act calling for the construction of a medical school at that location and a land deed.

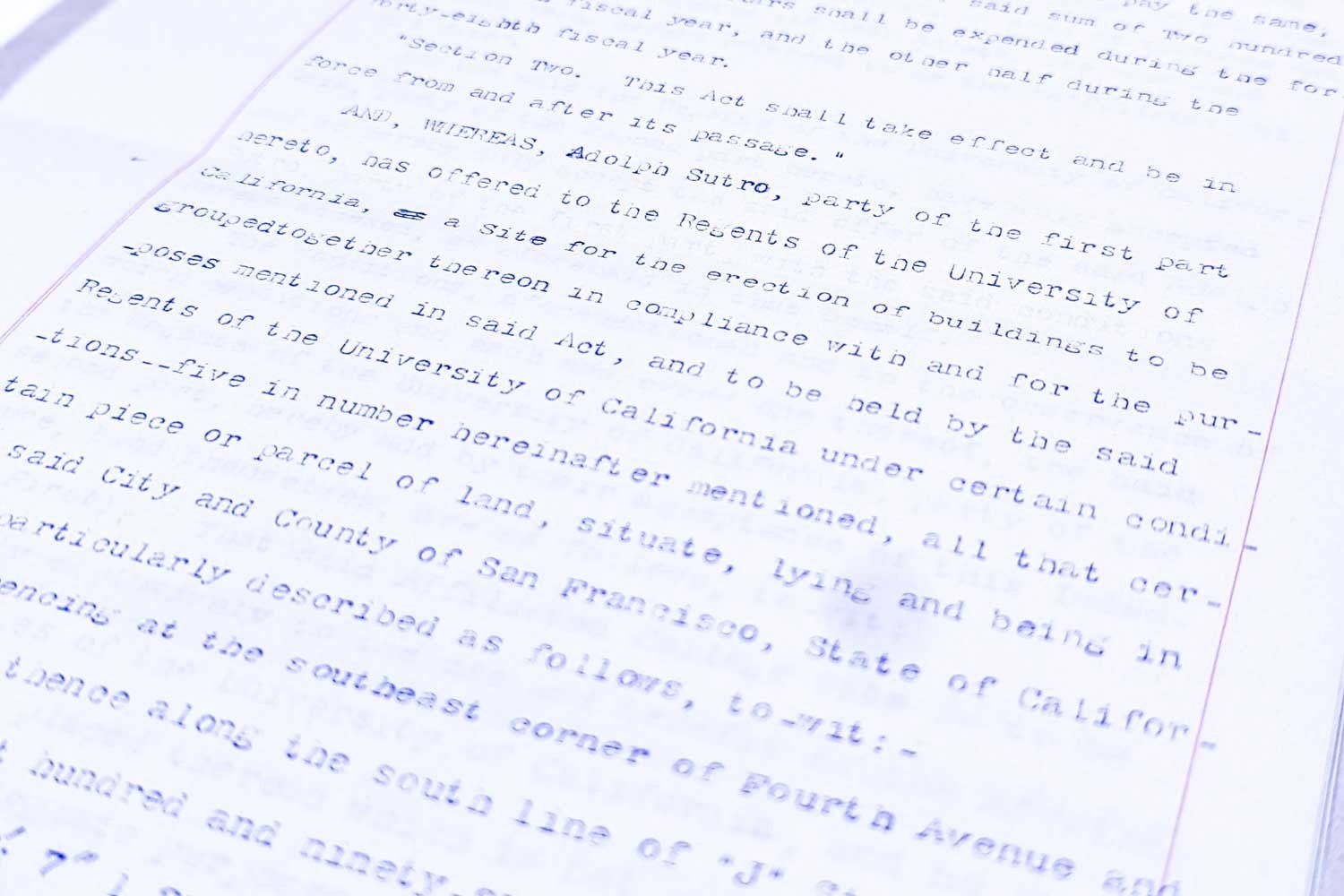

But it wasn’t just any deed. It was the deed for part of the Mount Parnassus space itself; 13 acres donated to the State of California by then San Francisco Mayor Adolph Sutro.

The mayor – who wouldn’t live long enough to see the new campus open – had made the gift with the explicit guidance that a UC medical school be constructed on the site.

With that, the UCSF seed was planted at Parnassus Heights.

Inside the copper box: The oldest known photograph of the Mount Parnassus site was found inside the time capsule placed within the original building’s cornerstone. It shows the leveling of the sand dunes by mule-drawn scoops in preparation for the new buildings.

The copper time capsule was opened 70 years later in 1967, when the original medical building was demolished to make way for newer, more modern facilities.

Inside the time capsule is a tag with the name of its manufacturer, Forderer Cornice Works in San Francisco.

A copy of the deed to the Mount Parnassus land. The full length document states Adolf Sutro’s official offer of the land to the University of California Regents.

“UCSF, which traces its roots back to Toland Medical College in North Beach before expanding to the west side of the city, was called the Affiliated Colleges at that time,” said Polina Ilieva, UCSF archivist and associate university librarian for collections. “Before they came together at Parnassus Heights, the schools of medicine, pharmacy and dentistry existed separately in private buildings across San Francisco. This was the first time they had been brought together in one place. It was significant.”

It was thought “the general University spirit” would grow with the schools under one roof, as written in the “Illustrated History of the University of California.” The campus was also originally intended to house the short-lived California Veterinary College and the Hastings College of the Law (now known as UC Law San Francisco), “but the [Hastings] faculty considered it too far from the city’s law courts and refused to move,” according to “A Pictorial History.”

The building for Hastings was instead converted into an anthropological museum.

It wasn’t just the law school that disliked the location, as the feeling about the new campus’ distance from San Francisco’s civic center was pervasive among public opinion in 1897.

Many decried its “remoteness…so far from the center of town,” as written in “A Pictorial History.” An editorial in a local newspaper the day after the cornerstone celebration lamented “the falling tears of Aesculapius (the Greek god of healing), weeping at the burial of a medical school amid the sand dunes.”

It should come as no surprise that Mount Parnassus and the surrounding area, mostly sand dunes and undeveloped grassland, was fairly inaccessible to most San Franciscans during those days. It stayed that way until rail and subsequent streetcar connections led to the development of the western portion of San Francisco, according to UCSF Executive Director of Physical Planning Kevin Beauchamp.

“They were lands that were beyond the center of the city in that day,” he said. “It was undeveloped because it was sand dunes. That was the natural state of the land there.”

The state of the land

A photo of the original buildings at the Mount Parnassus location, showing the natural sand dunes in the surrounding area.

Donations, daughters and dunes

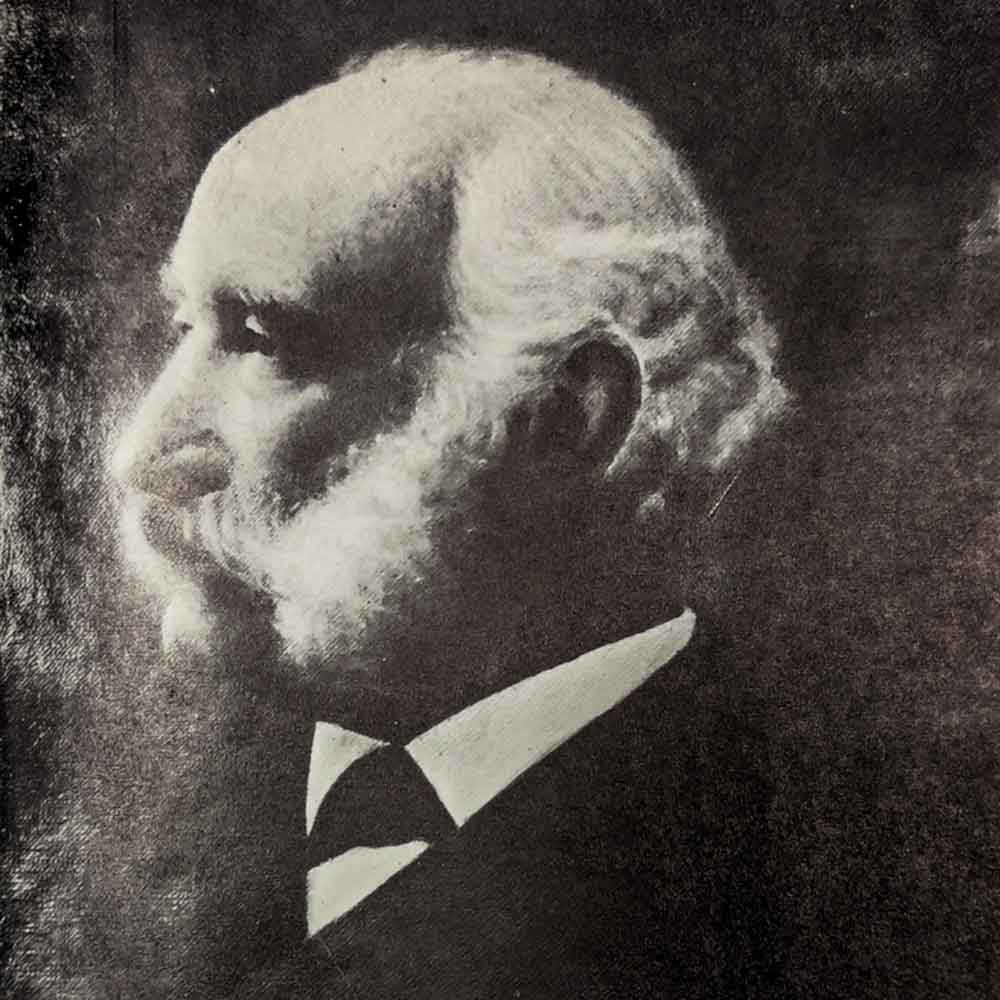

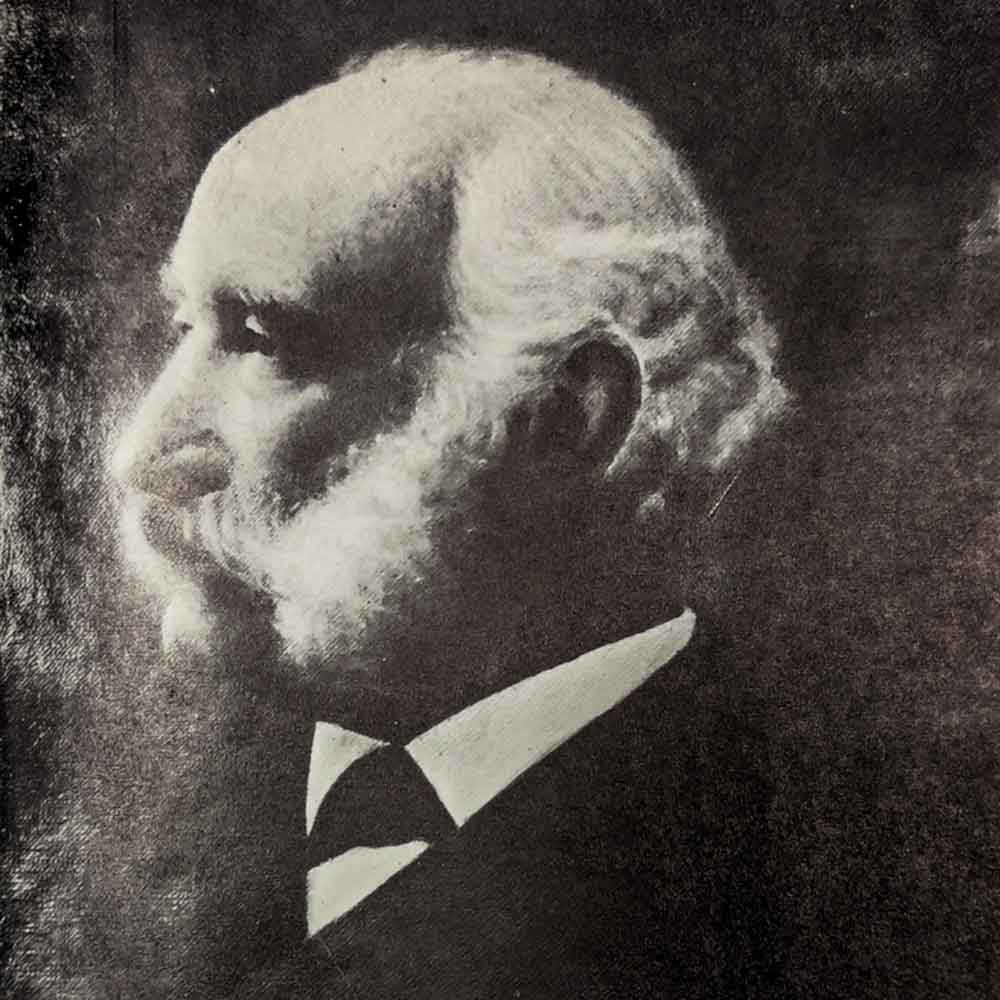

For Sutro, a Jewish engineer, becoming a real estate tycoon was surprising since he was penniless when he first arrived in the U.S. from Prussia in 1850.

He made the first of his fortune from the Comstock Lode silver mines in Nevada just a decade later, proposing the famous Sutro Tunnel to act as an underground drainage pipeline connected to the silver strike.

Returning to San Francisco in 1879, Sutro used his newfound riches to develop real estate like the famous Sutro Baths, an aquarium and amusement park, along with planting many trees across San Francisco.

“He just happened to be unique with an engineer’s mind that he also applied to the Sutro Baths and the aquarium,” said Jonathan Friedmann, PhD, director of the Jewish Museum of the American West. “These were modern marvels. He was very much an entrepreneur. He just kind of succeeded in ways that really were unprecedented.”

“The grandeur of nature is inspiring and spurs the scholar to higher achievements.”

Adolph Sutro, former San

Francisco mayor

He was elected San Francisco’s 24th mayor in 1895, serving only a two-year term in which he was remembered as “not an adept politician.” But it was what he did at the start of that term that had a lasting impact on the University of California. The Mount Parnassus site was originally a 26-acre property selected by Sutro to house the Sutro Library. However, as outlined in a September 1895 letter to the UC Regents, the site was split in two and 13 acres were given to the UC as an elevated site to build the Affiliated Colleges.

“Buildings erected on this spot will present a prominent landmark and may be seen not only by visitors to Golden Gate Park but also from all parts of the western half of the city,” Sutro wrote in the letter, noting the site’s aesthetic surroundings. “The grandeur of nature is inspiring and spurs the scholar to higher achievements,” he added.

Sutro also advocated for J Street to be renamed “Parnassus Avenue,” which came to fruition. However, the Sutro Library was never built as the former mayor intended.

Known much of his public life as a philanthropist, Sutro’s donation of the land to the UC also had a family tie: His eldest daughter, Emma Sutro Merritt, had received her medical degree from the University’s Medical Department in 1881 and was later a physician at the Children’s Hospital in San Francisco. “We might say his greatest accomplishment during those years was donating the land at Parnassus,” Friedmann said. “It was one of a number of land holdings that Sutro had.”

It was a very timely donation, too.

The California State Legislature had passed an act calling for the construction of the campus in March 1895, six months before Sutro’s letter to the UC Regents and a full two years before the cornerstone was laid. R. Beverly Cole, MD, the former dean of Toland Medical College and the Medical Department of the University of California, had lobbied California state lawmakers for the $250,000 in funds handed down through its passage and had a leading part in securing Sutro’s land donation.

“It all came together at the right time for the genesis of Parnassus Heights,” Ilieva said.

Building by mules

The oldest known photograph of the Mount Parnassus site was found inside the original cornerstone, showing the literal leveling of the sand dunes by mule-drawn scoops in preparation for the new buildings.

Three “large Romanesque buildings” to house the schools of medicine, pharmacy and dentistry were completed and occupied by October 1898. The School of Nursing, as many at UCSF know it today, began as a training school for nurses in 1907 and was officially established in 1939.

Without the land, we wouldn’t have had the facilities to pursue the academic mission.”

Ironically, after many in San Francisco questioned Mount Parnassus as the selected location of the Affiliated Colleges, it was that very “remote” location that allowed the schools to survive the devastating 1906 earthquake and fire.

While most of the city’s hospitals were destroyed, the Affiliated Colleges “rose to the occasion” with a severe shortage of medical facilities in San Francisco, as written in “The Centennial Record of the University of California.” The Medical Department set up emergency hospitals around the city in response to the tragedy, including one in the Medical School Building that eventually became the first University Hospital. Many physicians and nurses came to aid those injured who stayed in makeshift tents in Golden Gate Park.

It was a milestone moment for what had just years earlier been barren sand dunes.

“Without the land, we wouldn’t have had the facilities to pursue the academic mission,” Beauchamp said of Sutro’s 13-acre donation. “There’s something to be said about how we have grown beyond Parnassus. While Parnassus was so important in launching UCSF, it’s still vitally important as a place where education and patient care continue alongside research.”

Today, the revitalization of UCSF’s flagship campus is rooted in public service to San Francisco, the Bay Area and beyond – an anchor institution that continues to evolve with the groundbreaking of the new $4.3 billion UCSF Health Helen Diller Hospital, the construction of the UCSF Barbara and Gerson Bakar Research and Academic Building and the Greening Parnassus Heights Initiative.

Donations, daughters and dunes

For Sutro, a Jewish engineer, becoming a real estate tycoon was surprising since he was penniless when he first arrived in the U.S. from Prussia in 1850.

He made the first of his fortune from the Comstock Lode silver mines in Nevada just a decade later, proposing the famous Sutro Tunnel to act as an underground drainage pipeline connected to the silver strike.

Returning to San Francisco in 1879, Sutro used his newfound riches to develop real estate like the famous Sutro Baths, an aquarium and amusement park, along with planting many trees across San Francisco.

“He just happened to be unique with an engineer’s mind that he also applied to the Sutro Baths and the aquarium,” said Jonathan Friedmann, PhD, director of the Jewish Museum of the American West. “These were modern marvels. He was very much an entrepreneur. He just kind of succeeded in ways that really were unprecedented.”

“The grandeur of nature is inspiring and spurs the scholar to higher achievements.”

Adolph Sutro, former San

Francisco mayor

He was elected San Francisco’s 24th mayor in 1895, serving only a two-year term in which he was remembered as “not an adept politician.” But it was what he did at the start of that term that had a lasting impact on the University of California. The Mount Parnassus site was originally a 26-acre property selected by Sutro to house the Sutro Library. However, as outlined in a September 1895 letter to the UC Regents, the site was split in two and 13 acres were given to the UC as an elevated site to build the Affiliated Colleges.

“Buildings erected on this spot will present a prominent landmark and may be seen not only by visitors to Golden Gate Park but also from all parts of the western half of the city,” Sutro wrote in the letter, noting the site’s aesthetic surroundings. “The grandeur of nature is inspiring and spurs the scholar to higher achievements,” he added.

Sutro also advocated for J Street to be renamed “Parnassus Avenue,” which came to fruition. However, the Sutro Library was never built as the former mayor intended.

Known much of his public life as a philanthropist, Sutro’s donation of the land to the UC also had a family tie: His eldest daughter, Emma Sutro Merritt, had received her medical degree from the University’s Medical Department in 1881 and was later a physician at the Children’s Hospital in San Francisco. “We might say his greatest accomplishment during those years was donating the land at Parnassus,” Friedmann said. “It was one of a number of land holdings that Sutro had.”

It was a very timely donation, too.

The California State Legislature had passed an act calling for the construction of the campus in March 1895, six months before Sutro’s letter to the UC Regents and a full two years before the cornerstone was laid. R. Beverly Cole, MD, the former dean of Toland Medical College and the Medical Department of the University of California, had lobbied California state lawmakers for the $250,000 in funds handed down through its passage and had a leading part in securing Sutro’s land donation.

“It all came together at the right time for the genesis of Parnassus Heights,” Ilieva said.

Building by mules

The oldest known photograph of the Mount Parnassus site was found inside the original cornerstone, showing the literal leveling of the sand dunes by mule-drawn scoops in preparation for the new buildings.

Three “large Romanesque buildings” to house the schools of medicine, pharmacy and dentistry were completed and occupied by October 1898. The School of Nursing, as many at UCSF know it today, began as a training school for nurses in 1907 and was officially established in 1939.

Without the land, we wouldn’t have had the facilities to pursue the academic mission.”

Ironically, after many in San Francisco questioned Mount Parnassus as the selected location of the Affiliated Colleges, it was that very “remote” location that allowed the schools to survive the devastating 1906 earthquake and fire.

While most of the city’s hospitals were destroyed, the Affiliated Colleges “rose to the occasion” with a severe shortage of medical facilities in San Francisco, as written in “The Centennial Record of the University of California.” The Medical Department set up emergency hospitals around the city in response to the tragedy, including one in the Medical School Building that eventually became the first University Hospital. Many physicians and nurses came to aid those injured who stayed in makeshift tents in Golden Gate Park.

It was a milestone moment for what had just years earlier been barren sand dunes.

“Without the land, we wouldn’t have had the facilities to pursue the academic mission,” Beauchamp said of Sutro’s 13-acre donation. “There’s something to be said about how we have grown beyond Parnassus. While Parnassus was so important in launching UCSF, it’s still vitally important as a place where education and patient care continue alongside research.”

Today, the growth of UCSF’s flagship campus is rooted in public service to San Francisco, the Bay Area and beyond – an anchor institution that continues to evolve with the groundbreaking of the new $4.3 billion UCSF Health Helen Diller Hospital, the construction of the UCSF Barbara and Gerson Bakar Academic and Research Building and the Greening Parnassus Heights Initiative.