John Clements, MD, whose scientific discoveries helped save millions of newborns around the world from respiratory distress syndrome and whose boundless appetite for learning helped create the interdisciplinary culture at UC San Francisco, has died at the age of 101.

The tremendous impact of Clements' work was recognized in 1994 when he won the Lasker Clinical Medical Research Award for the discovery of lung surfactant, a soapy substance that reduces surface tension, so the tiny air sacs can deflate without collapsing.

Clements realized this first theoretically, then experimentally. Over a span of three decades, he and his colleagues at UCSF developed an artificial surfactant that led to the version that is still used today to keep premature infants alive.

Medicine, Music and Margot

Clements was revered by generations of colleagues and trainees at UCSF as much for his brilliance as for his humanity. He was a fine pianist, who often accompanied his wife Margot, an opera singer.

“I used to say that my father had three passions,” said his younger daughter Carol. “They were medicine, music and Margot.”

Clements gave freely of his time, serving as a mentor until his late 90s from an unassuming office on the 13th floor of Moffitt. When his mentees would get into a scientific pickle, he would look on with a wry smile and gently suggest something else for them to consider.

“Most of his mentoring style was encouraging you and figuring out ways to get you to talk through a problem,” said Chancellor Sam Hawgood, MBBS, who came to UCSF in 1982 to study with Clements. “And you’d eventually talk yourself into a solution.”

Michael Gropper, MD, PhD, who did his graduate work under Clements, remembers his presence at the weekly pulmonary physiology seminars at the Cardiovascular Research Institute (CVRI), which ranged across a vast clinical and scientific terrain.

“Whatever the topic, his was always the best question,” recalled Gropper, who is now chair of anesthesia. “I would be stunned by that, the insight that he had into this broad range of topics. Even to this day, I’ve never seen anything like it.”

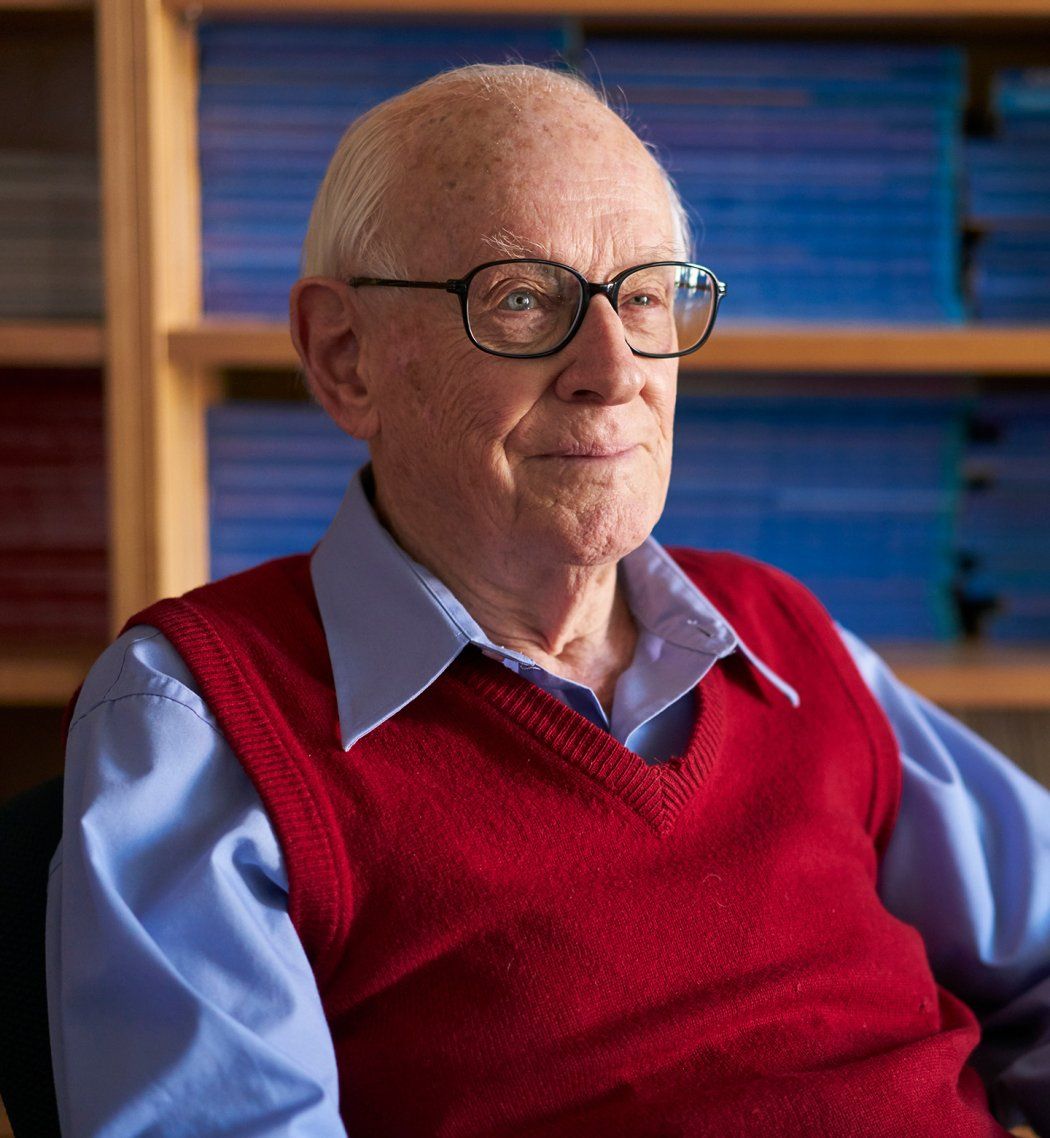

John Clements (left) with Chancellor Sam Hawgood (right) in 2014. Photo by Cindy Chew

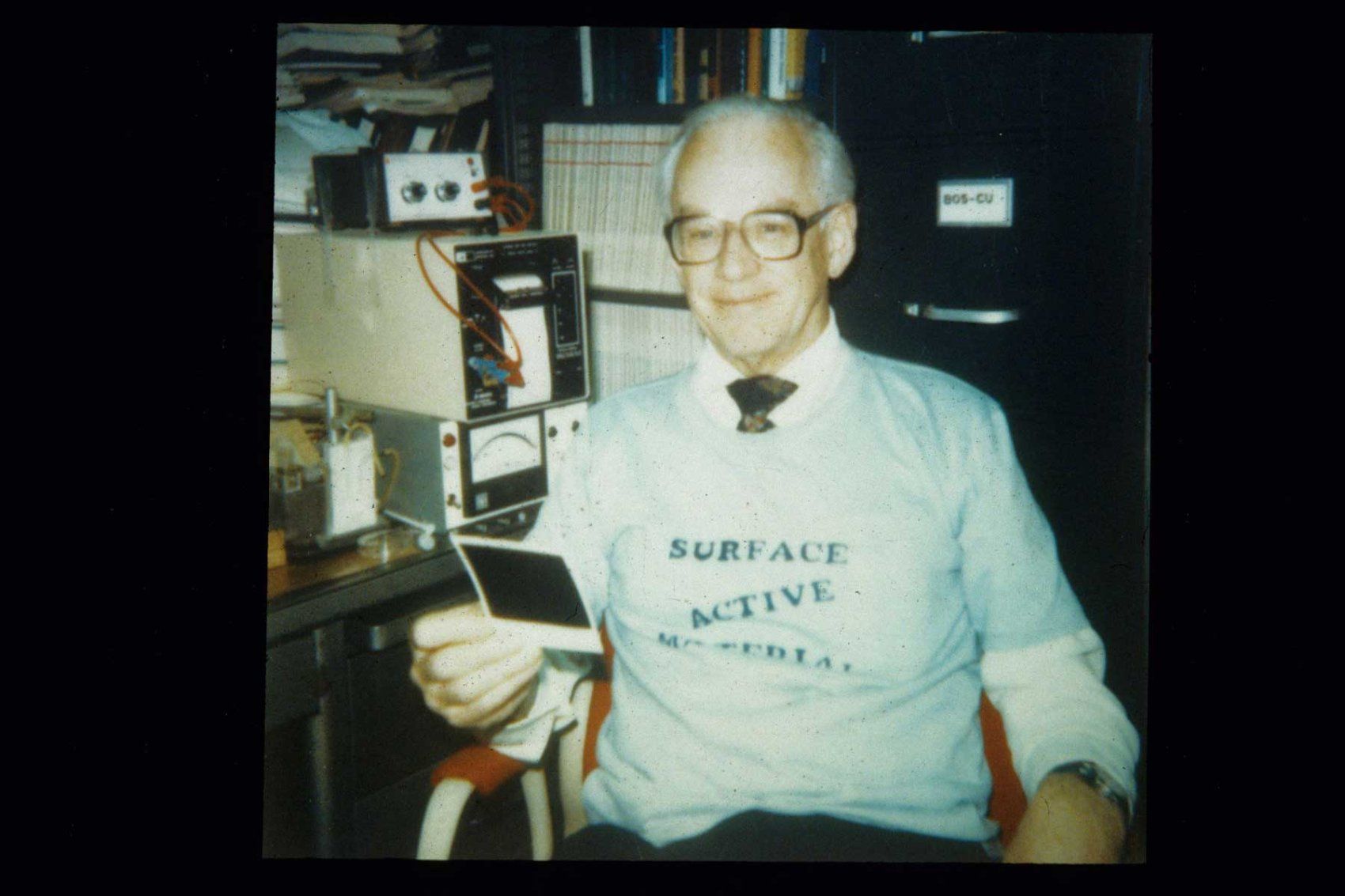

Clements in 1988.

Clements (right) with George Gregory (left) and Rod Phibbs (center right).

From nerve gas to a mysterious, life-saving substance

Clements began his research career in 1949 at the Medical Laboratories of the Army Chemical Center in Maryland, where he was assigned to look at the effects of nerve gas on the lungs. Always drawn to fundamental questions, he began to ponder how the lungs could breathe out without collapsing like a deflated balloon.

In 1956, he theorized that there must be something in the lungs that prevented this by lowering the surface tension of the liquid that coats the millions of gossamer, bubble-like air sacs, so they could easily deflate and then inflate with the next breath.

People just wanted to be around him and to learn from him and to work with him.”

He thought the substance worked by accumulating at the surface of the liquid, thereby reducing its tension.

Soon after, Mary Ellen Avery, a young researcher at Harvard realized that this material must be missing from the lungs of premature babies. And in 1959, she and Clements demonstrated it.

The following year, Clements was recruited to UCSF by Julius Comroe, MD, who founded the CVRI. Within a year, Clements had published the first article on the chemical composition of surfactant, a problem he would continue working on for decades.

In the 1960s and ‘70s Clements, became the leader of a group of basic scientists like himself, as well as clinicians George Gregory, MD, William Tooley, MD, Joseph Kitterman, MD, and Rod Phibbs, MD, who were building the field of neonatology.

“This was a remarkably respectful team, and while Clements would never claim leadership of it, he clearly was the intellectual giant that kept everyone together,” Hawgood said. “People just wanted to be around him and to learn from him and to work with him.”

The initial clinical breakthrough

Gregory sought out Clements whenever he got stuck. He would always identify the error and solve the problem in the gentlest way possible.

“I would go to his office and say, ‘John, I have this problem, what do you think about it?’ And John would always say, ‘Well, let’s go back to first principles,’” Gregory recalled. “He realized that other people weren’t as smart as he was, and he did everything he could to help them. He always was there and able to help.”

Clements helped Gregory develop continuous positive airway pressure, or CPAP, which had a major impact on infant mortality in the years before surfactant became available.

The device they came up with keeps the air pressure positive during expiration, preventing lung collapse, so the premature infants could breathe on their own. Refined versions of CPAP are used around the world today.

Fundamental science, transformative treatment

In time, Clements designed an artificial surfactant, Exosurf, which received approval from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1989 and underwent a clinical trial at UCSF.

A series of clinical trials funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) found that surfactants derived from animal lungs worked better, which is what is used today.

These advances have increased survival rates for extremely premature infants from 5% in the 1960s to 90% today.

“There’s probably not been a discovery in the lung division in the NIH that is more fundamental,” said Michael Matthay, MD, a lung expert at UCSF who worked closely with Clements. “It shows the potential for basic science being translated all the way to a transformative clinical treatment.”

An open-door retirement

Although he no longer kept his own research lab, Clements continued coming to work for many years after he retired in 2004.

Meshell Johnson, MD, chief of the division of pulmonary, critical care, sleep and allergy at the San Francisco VA Medical Center recalls the experience of spending time with him as otherworldly.

“He was someone who just made me think more than anyone I had come across. I would go into his office, and he would talk, and I’d emerge two hours later, but I never felt the time pass,” she said. “No mentor that I’ve had before or since has had those types of conversations with me.”

Once, she saw a group of mechanical engineers from Berkeley come by because they thought his knowledge of how surfactant lowers surface tension in the lungs could help them construct a bridge.

“It was always a series of these different people who were coming to bask in the knowledge of Dr. Clements,” she said. “Just come by and soak it in, and then head on out. He was just so generous that way.”

Clements, who died Sept. 3, is survived by his daughters, Carol and Christine.