83% of Students Go Into Science, Thanks to This Diversity Initiative

One of America’s oldest programs to bring students from different backgrounds into science research has changed the lives of thousands.

Corey Harwell climbs a flight of stairs to the UC San Francisco’s Medical Science Building entrance on Parnassus Avenue. From there, the city seems to unfurl to meet the Pacific Ocean.

It’s 1998, and the Tennessee State undergraduate has arrived for UCSF’s Summer Research Training Program. He takes the elevator to the 14th floor where he follows the signs to room 1471, the lab of then-UCSF professor and neuroscientist Cori Bargmann. He wonders if there has been a mix-up.

“I was a chemistry major, so I was sure I was going to be assigned to a biochemistry lab but, I was assigned to Cori’s lab, which studied the nervous system function of the small roundworms called C. elegans. I’d never even heard of them.”

“I told her I thought there’d been a mistake,” says Harwell, now a UCSF associate neurology professor. “Cori was gracious and suggested I spend a week in the lab. If I didn’t like it, we could go back to the program for another assignment. In just days, I was hooked and that’s why I chose neuroscience.”

At nearly 40 years old, the initiative is one of the oldest in the country working to diversify the pipeline of health and science researchers. Today, fewer than 1 in 3 doctoral students come from communities of color.

The 10-week program provides undergraduate students – particularly from underrepresented communities – the chance to conduct laboratory research at one of the nation’s leading health sciences research universities. Thousands of student-researchers have worked in UCSF’s laboratories thanks to the program. Remarkably, 83% go on to some form of higher education, and almost 1 in 10 will do so at UCSF. Roughly half will earn a PhD, and another 20% will become physicians.

The program has also produced at least three UCSF professors.

Attracting the best students from around the country

The Summer Research Training Program was started by biochemist and Professor Emeritus John A. Watson, PhD, one of UCSF’s first Black faculty members. Watson became the UCSF Medical School Assistant Dean for Student Affairs, where he pioneered diversity, equity and inclusion efforts. During his tenure, Watson increased the number of diverse students and faculty at the university thanks, in part, to initiatives such as the summer research program.

“He was a visionary,” says Carol Gross, PhD, a professor of cell and tissue biology in UCSF’s School of Dentistry who joined Watson in 1993 to lead the Summer Research Training Program. Today, she co-directs the program alongside Assistant Dean for Diversity and Learner Success in the Graduate Division D’Anne Duncan, PhD. The program attracts students from state universities, historically Black colleges and groups like the Society for Advancement of Chicanos/Hispanics & Native Americans in Science.

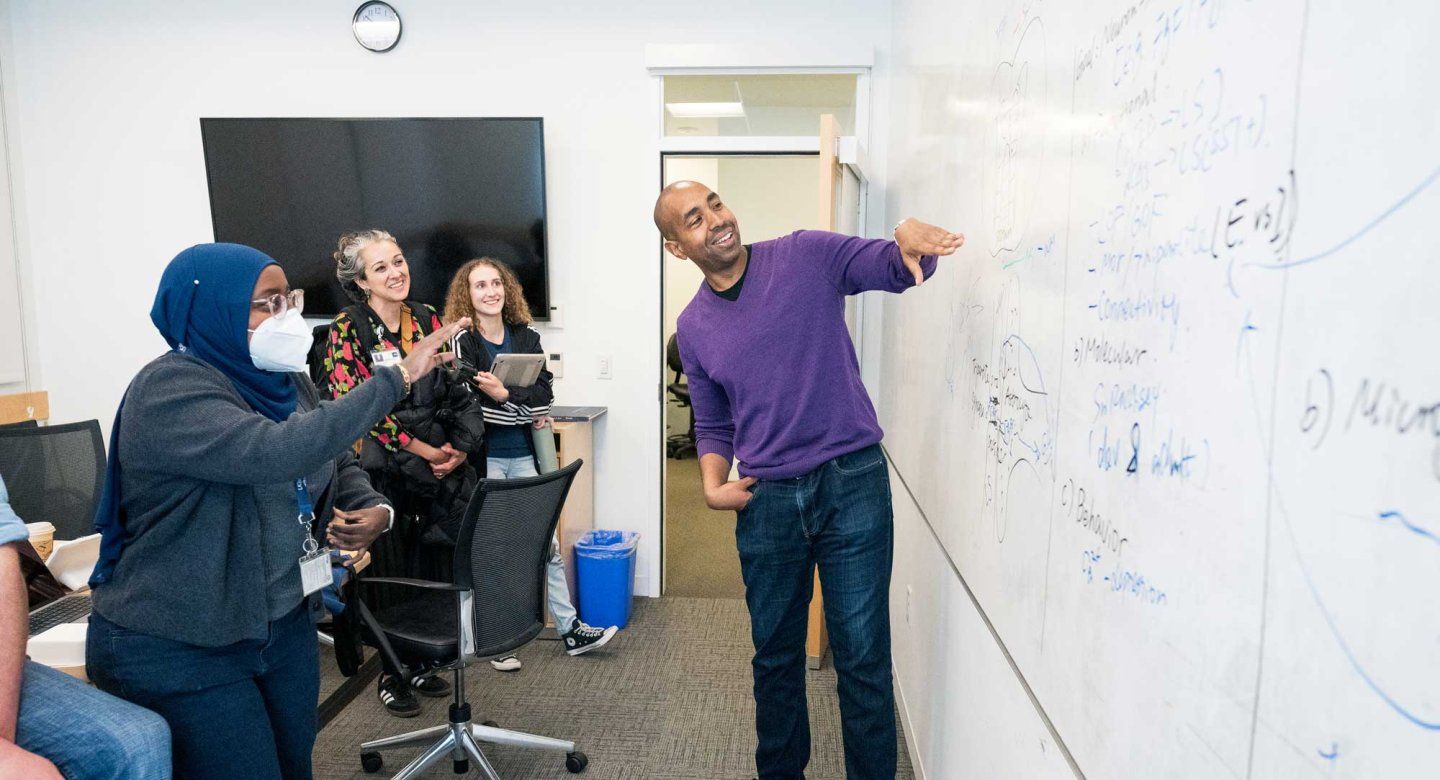

Summer Research Training Program students run their own experiments at UCSF, gathering data in fields like biology, chemistry and biophysics.

“This has always been faculty-led and, unlike many similar programs at other universities, spans various departments across the whole university,” explains Gross, who meticulously matches students one-on-one with faculty mentors based on interests each year. “We want to give students a sense of what it’s like to do high-level research, to ask and answer questions, and to see that they can function at one of the best universities in the world for basic science research.”

Embedded in the scientific community

Today, Harwell’s lab is unlocking new insights into brain cell development that could shape our understanding of chronic illnesses from epilepsy and autism to depression and addiction.

Through programs like this, we build a future for science that, with every successive iteration of students, there’s this growing diversity of possibilities of what it looks like to be a scientist.”

He is one of at least three UCSF professors to have come through the Summer Research Training Program, along with Assistant Professor of Biochemistry and Biophysics David Booth, PhD, and Associate Professor of Anatomy Saul Villeda, PhD.

“Participants in our Summer Research Training Program are embedded in the scientific community at UCSF,” Duncan explains. “They are also immersed in professional development activities that support their development as future scientists and researchers.”

Harwell’s discoveries shed light on an understudied part of the brain called the septum. The septum helps regulate behaviors related to addiction as well as motivation, anxiety and other emotions.

“It’s taken the lab into exciting new directions where we’re asking questions about how diverse brain cell types and circuits influence aspects of emotion or addiction,” Harwell says. “We’re also not just looking at changes in our genes but also how early life experience and the environment impact the development of brain circuits in the septum.”

Attracting the best students from around the country

The Summer Research Training Program was started by biochemist and Professor Emeritus John A. Watson, PhD, one of UCSF’s first Black faculty members. Watson became the UCSF Medical School Assistant Dean for Student Affairs, where he pioneered diversity, equity and inclusion efforts. During his tenure, Watson increased the number of diverse students and faculty at the university thanks, in part, to initiatives such as the summer research program.

“He was a visionary,” says Carol Gross, PhD, a professor of cell and tissue biology in UCSF’s School of Dentistry who joined Watson in 1993 to lead the Summer Research Training Program. Today, she co-directs the program alongside Assistant Dean for Diversity and Learner Success in the Graduate Division D’Anne Duncan, PhD. The program attracts students from state universities, historically Black colleges and groups like the Society for Advancement of Chicanos/Hispanics & Native Americans in Science.

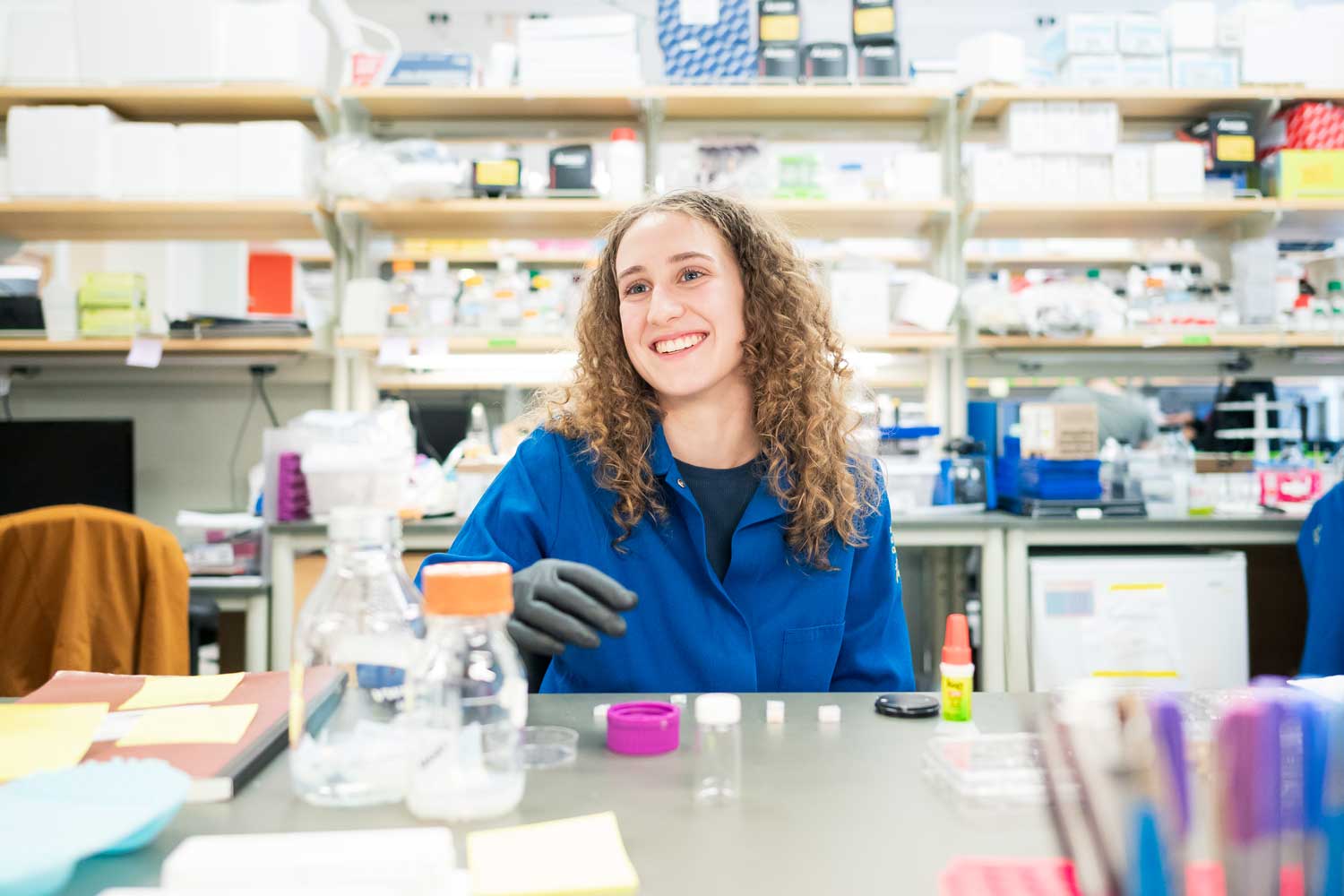

Summer Research Training Program students run their own experiments at UCSF, gathering data in fields like biology, chemistry and biophysics.

“This has always been faculty-led and, unlike many similar programs at other universities, spans various departments across the whole university,” explains Gross, who meticulously matches students one-on-one with faculty mentors based on interests each year. “We want to give students a sense of what it’s like to do high-level research, to ask and answer questions, and to see that they can function at one of the best universities in the world for basic science research.”

Embedded in the scientific community

Today, Harwell’s lab is unlocking new insights into brain cell development that could shape our understanding of chronic illnesses from epilepsy and autism to depression and addiction.

He is one of at least three UCSF professors to have come through the Summer Research Training Program, along with Assistant Professor of Biochemistry and Biophysics David Booth, PhD, and Associate Professor of Anatomy Saul Villeda, PhD.

Through programs like this, we build a future for science that, with every successive iteration of students, there’s this growing diversity of possibilities of what it looks like to be a scientist.”

“Participants in our Summer Research Training Program are embedded in the scientific community at UCSF,” Duncan explains. “They are also immersed in professional development activities that support their development as future scientists and researchers.”

Harwell’s discoveries shed light on an understudied part of the brain called the septum. The septum helps regulate behaviors related to addiction as well as motivation, anxiety and other emotions.

“It’s taken the lab into exciting new directions where we’re asking questions about how diverse brain cell types and circuits influence aspects of emotion or addiction,” Harwell says. “We’re also not just looking at changes in our genes but also how early life experience and the environment impact the development of brain circuits in the septum.”

What’s it look like to be a scientist?

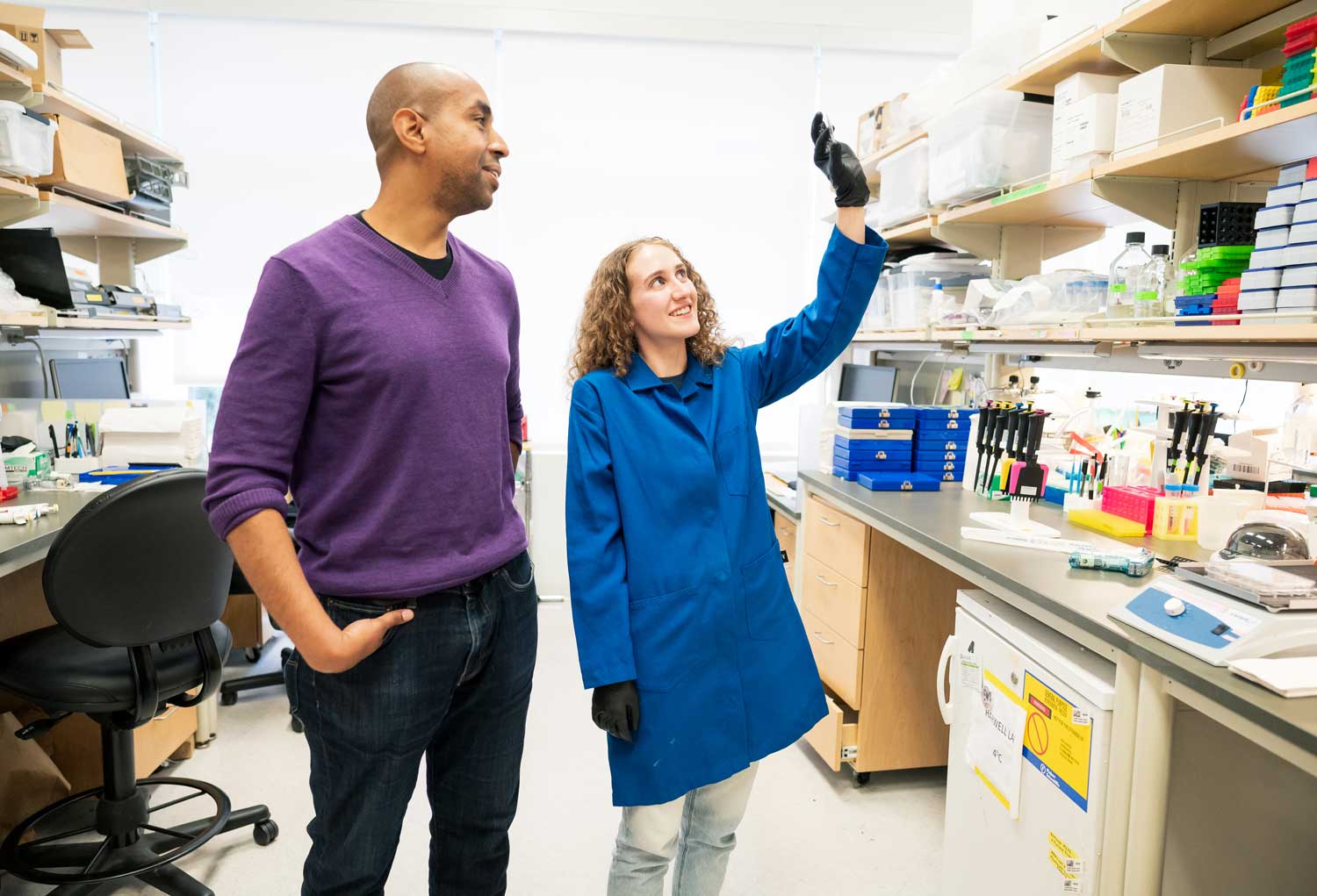

Melissa Solem, a University of Minnesota undergraduate, is part of the current Summer Research Training Program. She is working on one of Harwell’s newer projects: using models to study the effects of prenatal and early infant exposure to fentanyl on brain circuit development.

She plans on applying to graduate school and is particularly interested in how chemicals in the environment shape our health.

“My family works in agriculture, so we always hear about some pesticides and links to cancer,” says Solem, who will be the first in her family to earn a PhD. “That’s made me interested in looking at the cellular or molecular mechanism behind that or links between air pollution and cognitive issues later in life.”

Harwell knows that investing in students like Solem helps advance a future in which everyone can see themselves behind the bench.

“Starting out in science can be intimidating – it feels like everyone else knows so much, and that feeling can be magnified for students who haven’t had opportunities to know about these spaces,” Harwell explains. “The hope is that through programs like this, we build a future for science that, with every successive iteration of students, there’s this growing diversity of possibilities of what it looks like to be a scientist.”

At her lab bench, Solemn has sketched diagrams of preliminary results onto lined paper in preparation for presentations she’ll make to fellow summer students at the close of the program. She’s worked with Harwell and postdoctoral scholar Rhiana Simons, PhD, to refine the talk. Many students use the summer experience to build their resumes for graduate school application.

For Harwell, who also hosts high school students from other UCSF summer programs, mentorship is a commitment he hopes to instill in others.

“I think it’s still very easy for me to conceive of what it’s like to come into a lab space and feel like you don’t know how to do anything,” he says. “Mentorship and teaching are part of the culture of my lab. It’s okay to not know something and to feel comfort in that because being at the edge of your knowledge is actually what this career is all about.”

Dec. 30, 2024 correction: About 1 in 3 PhD students come from communities of color. This figure was updated from about 1 in 10.