Scientists May Have Found How to Diagnose Elusive Neuro Disorder

The discovery of a unique pattern of proteins in the spinal fluid of patients may help with earlier diagnosis and new treatments for progressive supranuclear palsy.

Progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), a mysterious and deadly neurological disorder, usually goes undiagnosed until after a patient dies and an autopsy is performed. But now, UC San Francisco researchers have found a way to identify the condition while patients are still alive.

A study appearing in Neurology on July 3 has found a pattern in the spinal fluid of PSP patients, using a new high-throughput technology that can measure thousands of proteins in a tiny drop of fluid.

Researchers hope the protein biomarkers will lead to the development of a diagnostic test and targeted therapies to stall the disease’s fatal trajectory.

The disorder crossed the public’s radar 25 years ago, when Dudley Moore, the star of “10” and “Arthur,” shared his PSP diagnosis. It is frequently mistaken for Parkinson’s disease, but PSP develops faster, and patients do not respond to treatments for Parkinson’s. Most PSP patients die within about seven years after their symptoms have started.

Diagnosis is key, because treatments

work best early on

PSP is believed to be triggered by a buildup of tau proteins that causes cells to weaken and die. It is a type of frontotemporal dementia (FTD) that affects cognition, movement and behavior. Its hallmark symptoms include poor balance with frequent backward falls and difficulties moving eyes up and down.

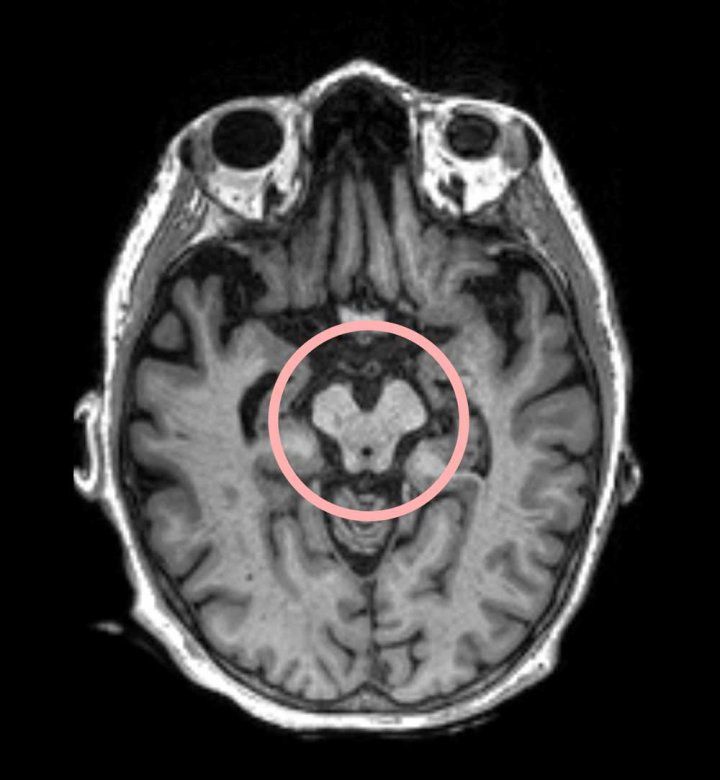

“Unlike Alzheimer’s disease, there are no tau scans, blood tests or MRIs that provide a definitive diagnosis of PSP. For many patients the disease goes unnoticed,” said co-senior author Julio Rojas, MD, PhD, of the UCSF Department of Neurology, Memory and Aging Center and the Weill Institute for Neurosciences.

“When new medications are approved for PSP, the best chance for patients will be receiving treatment at the earliest phase of the disease when it is most likely to be effective,” he said.

The inability to identify PSP has hampered the development of new treatments, according to co-senior author Adam Boxer, MD, PhD, endowed professor in memory and aging at the UCSF Department of Neurology, and director of the Alzheimer’s Disease and Frontotemporal Dementia Clinical Trials Program.

“Previous research has underscored the value of several non-specific neurodegeneration biomarkers in PSP, but they have had limited sensitivity and specificity for diagnosis, particularly at this critical early disease stage,” he said.

Proteins are associated with neurodegeneration

The researchers measured the protein biomarkers using the high-throughput technology for protein analysis, which is based on molecules that bind to proteins with high selectivity and specificity.

The study had 136 participants, with an average age of 70, and included patients from UCSF and other institutions with symptoms that are consistent with PSP, as well as autopsy-confirmed PSP cases. Scientists compared biomarkers from these cases to the living patients, as well as to healthy participants and to patients with other forms of FTD.

The researchers found lower levels of most proteins in those with confirmed or suspected PSP, compared to the healthy participants in the study. The protein signature of the autopsy-confirmed PSP cases also differed from the autopsy-confirmed cases of other forms of FTD, as well as the living patients.

All those with confirmed or suspected PSP had higher levels of proteins associated with neurodegeneration. The researchers also found some inflammatory proteins that correlated with disease severity and decreased proteins relevant to several critical brain cell functions that could be manipulated with future therapies.

“This work aims to create a framework for using these newly identified proteins in future clinical trials,” said first author, Amy Wise, formerly of the UCSF Department of Neurology, and the Memory and Aging Center, and currently a medical student at UC Davis. “We hope to reach a point where a single biomarker, or a panel of biomarkers from a blood test or lumbar puncture, can provide definitive diagnostic and prognostic results for PSP.”

Co-Authors and Disclosures: Please see the paper.

Funding: NIH/NIA R01AG038791, U19AG063911, NIH/NIA K23AG59888, NIH R01AG078457, U19AG063911, R01AG073482, R56AG075744, R01AG038791, RF1AG077557, R01AG071756, U01AG045390, P01AG019724, P30AG062422, NINDS/NIH K08NS105916, NIH/NIA K23AG059891, NIH/NINDS U01NS102035, NIH/NIA R01AG038791, NIH K23AG073514. Rainwater Charitable Foundation, GHR Foundation, Bluefield Project to Cure FTD, Gates Ventures, Association for Frontotemporal Degeneration, Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation, Alzheimer’s Association, AlzOut – Alzheimer’s Research, John Douglas French Alzheimer’s Foundation.

Diagnosis is key, because

treatments work best early on

PSP is believed to be triggered by a buildup of tau proteins that causes cells to weaken and die. It is a type of frontotemporal dementia (FTD) that affects cognition, movement and behavior. Its hallmark symptoms include poor balance with frequent backward falls and difficulties moving eyes up and down.

“Unlike Alzheimer’s disease, there are no tau scans, blood tests or MRIs that provide a definitive diagnosis of PSP. For many patients the disease goes unnoticed,” said co-senior author Julio Rojas, MD, PhD, of the UCSF Department of Neurology, Memory and Aging Center and the Weill Institute for Neurosciences.

“When new medications are approved for PSP, the best chance for patients will be receiving treatment at the earliest phase of the disease when it is most likely to be effective,” he said.

The inability to identify PSP has hampered the development of new treatments, according to co-senior author Adam Boxer, MD, PhD, endowed professor in memory and aging at the UCSF Department of Neurology, and director of the Alzheimer’s Disease and Frontotemporal Dementia Clinical Trials Program.

“Previous research has underscored the value of several non-specific neurodegeneration biomarkers in PSP, but they have had limited sensitivity and specificity for diagnosis, particularly at this critical early disease stage,” he said.

The researchers measured the protein biomarkers using the high-throughput technology for protein analysis, which is based on molecules that bind to proteins with high selectivity and specificity.

The study had 136 participants, with an average age of 70, and included patients from UCSF and other institutions with symptoms that are consistent with PSP, as well as autopsy-confirmed PSP cases. Scientists compared biomarkers from these cases to the living patients, as well as to healthy participants and to patients with other forms of FTD.

The researchers found lower levels of most proteins in those with confirmed or suspected PSP, compared to the healthy participants in the study. The protein signature of the autopsy-confirmed PSP cases also differed from the autopsy-confirmed cases of other forms of FTD, as well as the living patients.

All those with confirmed or suspected PSP had higher levels of proteins associated with neurodegeneration. The researchers also found some inflammatory proteins that correlated with disease severity and decreased proteins relevant to several critical brain cell functions that could be manipulated with future therapies.

“This work aims to create a framework for using these newly identified proteins in future clinical trials,” said first author, Amy Wise, formerly of the UCSF Department of Neurology, and the Memory and Aging Center, and currently a medical student at UC Davis. “We hope to reach a point where a single biomarker, or a panel of biomarkers from a blood test or lumbar puncture, can provide definitive diagnostic and prognostic results for PSP.”

Co-Authors and Disclosures: Please see the paper.

Funding: NIH/NIA R01AG038791, U19AG063911, NIH/NIA K23AG59888, NIH R01AG078457, U19AG063911, R01AG073482, R56AG075744, R01AG038791, RF1AG077557, R01AG071756, U01AG045390, P01AG019724, P30AG062422, NINDS/NIH K08NS105916, NIH/NIA K23AG059891, NIH/NINDS U01NS102035, NIH/NIA R01AG038791, NIH K23AG073514. Rainwater Charitable Foundation, GHR Foundation, Bluefield Project to Cure FTD, Gates Ventures, Association for Frontotemporal Degeneration, Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation, Alzheimer’s Association, AlzOut – Alzheimer’s Research, John Douglas French Alzheimer’s Foundation.