Chancellor Emeritus Julius Krevans, a Transformative Leader at UCSF, Dies at 91

Portrait of Julius Krevans while he was chancellor of UCSF.

Chancellor Emeritus Julius “Julie” R. Krevans, MD, a distinguished physician and educator whose transformative leadership helped propel UC San Francisco into greatness during the past generation, died peacefully in Maine on July 12. He was 91.

Krevans was widely recognized as a national leader in guiding health policy and medical education and championing science, which spawned the biotechnology industry, co-led by a UCSF scientist, and led to the awarding of Nobel Prizes to UCSF scientists. He received numerous honors and awards for his achievements, including the Abraham Flexner Award, given annually to a single individual to recognize outstanding contributions to medical education.

At UCSF, Krevans was appointed dean of the School of Medicine in 1971 and UCSF’s fifth chancellor in 1982. During his 11-year tenure as chancellor, he spearheaded the University’s remarkable growth and development across education, research, patient care and community service. He also boosted UCSF’s efforts to attract women and minority students to careers in health sciences and strengthened its community outreach programs.

In 1993, Krevans was awarded the UCSF Medal, its highest honor, for his contributions locally and nationally over more than two decades.

“Julie was a true giant and a transformative leader at UCSF at a time of great university growth,” says UCSF Chancellor Sam Hawgood, MBBS. “He left a tremendous legacy at UCSF and will be missed by all.”

Nurturing a Biotech Industry

One of his greatest legacies as dean and chancellor was his leadership in 1973 when UCSF scientist Herbert Boyer, PhD, in collaboration with Stanley Cohen, MD, of Stanford University, discovered recombinant DNA.

UCSF Memorial for Julius Krevans

UCSF will host a memorial tribute to honor Chancellor Emeritus Julius Krevans later this year. Check back at UCSF news for details.

The family asks that donations in his name go to the Julius and Patricia Krevans Graduate Fund.

“Julie Krevans fostered the use of this technology, and its widespread use within the school, which revolutionized biology and created a burgeoning industry,” says William Rutter, PhD, chair of the Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics from 1968 to 1982 who retired from UCSF in 1991.

UCSF’s history of fostering biotech innovation and entrepreneurship, Rutter points out, largely began with Genentech, which initially occupied laboratory space at the University during the early phase of its existence. In 1981, Rutter and two colleagues co-founded Chiron where they developed the first recombinant vaccine to treat Hepatitis B, worked on the first sequencing of the HIV genome in 1984, and discovered, sequenced and cloned the Hepatitis C virus in 1987. This work paved the way for the development of diagnostic tests, therapeutic drugs, and vaccines against these viruses, and pioneered other projects aimed at therapy of cancer and metabolic disease.

Since then, UCSF has spun off more than 100 biotech companies – more than any other university.

Seeing the Future of Health Sciences

Bruce Alberts, PhD, credits Krevans for articulating a compelling vision for the future that attracted many faculty to UCSF including himself. Alberts, who went on to co-found the successful Science and Health Education Partnership at UCSF and serve as president of the National Academy of Sciences, was recruited from Princeton University in 1976 to UCSF instead of Harvard.

As dean, Krevans remained active in clinical practice by taking an annual rotation in hematology at Moffitt Hospital and the Cancer Research Institute.

“Julie had a warm, charismatic personality, and spending time with him convinced each of us [recruited then] that this university had a future that would be enormously different than its past,” Alberts said. “In fact, thanks in large part to Julie’s two decades of leadership, it all turned out much better than any of us had imagined.”

Henry Bourne, PhD, emeritus professor and former chair of the Department of Pharmacology, considers Krevans among a handful of UCSF’s most game-changing leaders.

In his book, Paths to Innovation: Discovering Recombinant DNA, Oncogenes, and Prions, in One Medical School, in One Decade, Bourne summed up UCSF’s success like this: “By the 1980s, a series of extraordinary events had transformed UCSF into a world leader in fundamental biological research and training, making it one of the best medical schools in the U.S. and the world. UCSF scientists had revolutionized biology by discovering recombinant DNA, created a burgeoning biotechnology industry by exploiting the new technology to synthesize hormones in microorganisms, discovered the first mutant genes that trigger cancer, and found an entirely new and controversial mechanism for transmission of disease by protein particles called prions. These discoveries changed biology and medicine forever, at UCSF and in the world at large.”

Krevans had the privilege as chancellor to celebrate in 1989 when the Nobel Prize was awarded to J. Michael Bishop, MD, and Harold Varmus, MD — the first ever won by UCSF scientists — for their discovery of proto-oncogenes, normal genes that can be converted to cancer genes by genetic damage.

A Period of Growth and Innovation

Lloyd “Holly” Smith, MD, chair emeritus of the Department of Medicine, recalls Krevans as driving the highly successful celebration of UCSF’s 125th anniversary, establishing the UCSF Foundation to engage community leaders to gain both political and financial support for current and future activities, overseeing the building of the Long Hospital addition to Moffitt Hospital on the Parnassus campus and acquiring Mount Zion and Laurel Heights. Krevans also was a major participant in establishing the UCSF-affiliated J. David Gladstone Institutes.

“Throughout all of these prodigies, Julie maintained his affable light-hearted affect and upbeat personality,” Smith says. “It was said that he could tell you more bad news with better grace than anyone else, and leave you chuckling at one of his bon mots.”

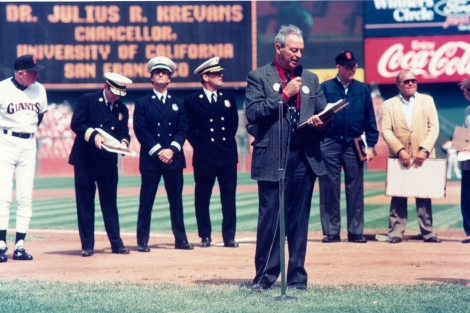

Krevans addresses the crowd at Candlestick Park, where he threw out the first pitch at a Giants game.

After retiring in 1993, Krevans had more time to enjoy one of his favorite activities, sailing. Photo courtesy of Krevans family

Krevans worked tirelessly for faculty to secure funding and find space on and off the then overcrowded Parnassus campus to support their research. He persuaded donors and non-federal sources to support the controversial research of Stanley Prusiner, MD, professor of neurology, when the National Institutes of Health and many others in the scientific community did not. Prusiner later won the Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine in 1997 for his discovery of prions. Prusiner acknowledged Krevans’ support in his autobiography, Madness and Memory.

Krevans is remembered for his mentorship and friendship. Chancellor Hawgood, who began his postdoctoral fellowship at UCSF in 1982, the same year that Krevans was appointed as chancellor, recalls the influence he had on him. “As a very young physician-scientist early in my career, I still remember the personal interest Julie showed in me. Now trying to follow in his footsteps, I find this personal touch and true humanity even more remarkable,” Hawgood says.

In his free time, Krevans enjoyed baking bread, sailing, golfing and cheering on the San Francisco Giants. As chancellor, he was delighted to be invited to throw out the first pitch at a Giants game at Candlestick Park.

Krevans retired as chancellor in 1993. On his day of retirement, San Francisco Mayor Jordan designated May 19 as Julius R. Krevans Day.

“My dad was incredibly happy and proud of his many years with UCSF,” says his daughter, Sarah Krevans. “He loved to discuss the tremendous growth and success of the research programs, the quality of the faculty and students and the impact the clinical programs had on people's lives.”

From New York Son to National Leader

Krevans was born on May 1, 1924, in New York. He received his AB degree from New York University in 1944, and his MD degree from New York University’s School of Medicine in 1946.

“My dad was born the child of two immigrants; his first two languages were not English,” says Sarah Krevans. “He rose to be dean of one of the finest medical schools in the world, saw his five children finish college and graduate school, and married the love of his life. He lived a great life.”

Krevans, right, joins then-Surgeon General C. Everett Koop for a press conference.

Krevans enlisted in the Army in 1948, where he served in the Philippine Islands and the Walter Reed Hospital. He was discharged from the Army in 1950, and then began a long career in academic medicine at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine as a fellow in hematology.

At Johns Hopkins, Krevans rapidly advanced from a beginning instructor to professor of medicine and dean for academic affairs. As an active research investigator and clinician, he served as the director of the Johns Hopkins Blood Bank and subsequently as physician-in-chief for Baltimore City Hospitals.

Krevans has served on numerous national boards and committees, including the board of the National Academy of Sciences' Institute of Medicine (recently renamed the National Academy of Medicine), and the American Board of Internal Medicine. He served as a director of the Clinical Scholar Program, and of the James Picker, and Bank of America-Giannini Foundations. He was a member of the Association of American Physicians, the San Francisco Planning and Urban Renewal Association, and the San Francisco Zoological Society. He was also the chair of the American Board of Internal Medicine's Committee on the Humanistic Qualities in the Internist. From 1980-1981, he served as the national chair of the Association of American Medical Colleges, helping develop public policy for the organization.

Among his other honors, Krevans was named Alumnus of the Year by his alma mater, the NYU School of Medicine. He also received the American College of Cardiology Convocation Medal (1984), and an Honorary Degree of Doctor of Humane Letters from Rush University. He was made a Commander in the Order of Merit in the Republic of Italy and a Master in the American College of Physicians.

Krevans is survived by his wife of 65 years, Patricia Krevans; his five children, Nita Krevans, chairman of the Department of Classical and Near Eastern Studies at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis; Julius R. Krevans, Jr., MD, an internist in Bar Harbor, Maine; Rachel Krevans, JD, a partner at Morrison and Foerster in San Francisco; Sarah Krevans, president and chief operating officer at Sutter Health in Sacramento; Nora Krevans, a learning specialist in the Graduate and Professional Programs at the University of New England; and seven grandchildren.

For more campus news and resources, visit Pulse of UCSF.