How Much Will I Be Charged at the Emergency Room?

UCSF Study Examines Wide Range of ER Bills, Highlights Need for Better-Informed Patients

It’s a basic, reasonable question: How much will this cost me? For patients in the emergency room, the answer all too often is a mystery.

Emergency departments play a critical role in health care, yet consumers typically know little about how medical charges are determined and often underestimate their financial responsibility – then are shocked when the hospital bill arrives.

In a new study published online on Feb. 27 in PLOS ONE, a team of researchers led by UC San Francisco identified giant price swings in patient charges for the 10 most common outpatient conditions in emergency rooms across the country.

Out-of-pocket patient charges ranged from $4 to $24,110 for sprains and strains; from $15 to $17,797 for headache treatment; from $128 to $39,408 for kidney stone treatment; from $29 to $29,551 for intestinal infections; and from $50 to $73,002 for urinary tract infections.

While the study was not designed to evaluate specific reasons behind the cost variations, the authors noted previous research attributing cost differences to factors such as geographic location and provider reimbursement variations.

More transparency in hospital charges is needed, the authors said, and consumers should be better informed about the costs of their medical care.

The study, representing an estimated 76 million emergency department visits between 2006 and 2008, is the first to demonstrate a large, nationwide variability in charges for common emergency department outpatient conditions, according to the researchers. The analysis uses data from the 2006-2008 Medical Expenditures Panel Survey from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Inquiring About Medical Costs

Amid escalating health care costs and a growing burden of medical debt among many Americans, cost controls and transparency in the nation’s emergency rooms are increasingly important, the authors said, particularly for medical conditions that are less time-sensitive.

Renee Y. Hsia, MD

Renee Y. Hsia, MD“Our study shows unpredictable and wide differences in health care costs for patients,’’ said senior author Renee Y. Hsia, MD, an assistant professor of emergency medicine at UCSF. She is also an attending physician in the emergency department at San Francisco General Hospital & Trauma Center.

“Patients actually have very little knowledge about the costs of their health care, including emergency visits that may or may not be partially covered by insurance,’’ she said. “Much of this information is far too difficult to obtain.’’

The cost of health care has increasingly been at the forefront of economic, political and medical debate. But especially when it comes to emergency rooms (ERs) – visited by an estimated one in five Americans each year – patients as well as their physicians are often in the dark about billable charges.

For consumers with health insurance, escalating ER charges are resulting in larger deductibles and co-payments. And for the ranks of uninsured patients, who disproportionately rely on the emergency department for non-emergency care, higher ER charges result in a larger proportion of self-pay responsibility.

Among key findings from the study:

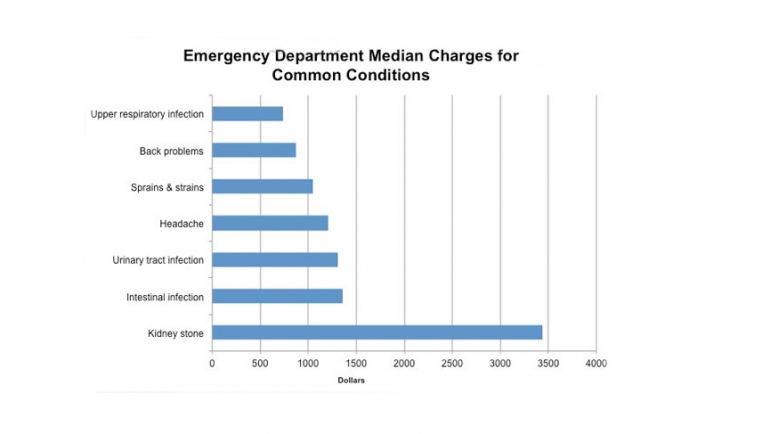

- The median charge for total outpatient conditions was $1,233.

- Upper respiratory infections had the lowest median charge: $740.

- A kidney stone condition had the highest median price: $3437.

- Uninsured patients were charged the lowest median price ($1,178) followed by those with private insurance ($1,245) and Medicaid ($1,305).

“While most patients with time-sensitive conditions such as acute myocardial infarction, stroke, or sepsis may not be in a position to make decisions about their care based on costs or charges, there are many situations in which patients could reasonably inquire about the potential financial implications of their medical care before making treatment decisions,’’ the authors wrote.

Study Methodology

The study focused on adults 18 to 64 years old, the demographic at the highest risk of facing the largest out-of-pocket charges. It excluded people 65 and older because most such patients are covered by Medicare. And it excluded visits resulting in hospital admission.

Altogether, the researchers looked at the total charges – medical care, tests and treatment – for 8,303 patients, nearly half of them privately insured.

The charges do not represent the amount patients or insurers reimburse providers, but rather the total charge that patients or their insurance providers are billed. Because of the complex survey design, the number of patients analyzed in the sample was weighted to provide the total estimated number of ER visits during the study timeframe.

The most common outpatient conditions were sprains and strains, “other injuries,’’ and “open wounds of extremities.’’ Many patients suffered from hypertension, asthma or high cholesterol.

Co-authors are Nolan Caldwell, MD of Stanford University; Tanja Srebotnjak, PhD, of the Ecologic Institute in San Mateo; and Tiffany Wang, BA, of the University of Minnesota Medical School.

Support for the study was provided by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health (UCSF-CTSI Grant Number KL2TR000143), and the UCSF Center for Healthcare Value.