Struggling Sea Lions May Benefit from UCSF Neuroscience Research

First-Ever Attempt at Cell Therapy for Marine Mammals with Epilepsy Stems from Decades of Research and a Unique Bay Area Collaboration

Cronutt, a 7-year-old sea lion, suffered from epilepsy due to poisoning from toxic algae. Photo by Dianne Cameron

A cellular therapy for epilepsy developed at UC San Francisco has been employed for the first time in a sea lion with intractable seizures caused by ingesting toxins from algal blooms. The procedure is the first-ever attempt to treat naturally occurring epilepsy in any animal using transplanted cells.

The 7-year-old male sea lion, named Cronutt, first beached in San Luis Obispo County in 2017 and was rescued by The Marine Mammal Center (TMMC), based in Sausalito, Calif. His epilepsy is due to brain damage caused by exposure to domoic acid released by toxic algal blooms. Each year, domoic acid poisoning affects hundreds of marine mammals, including both sea lions and sea otters, up and down the West Coast, a problem that is on the rise as climate change warms the world’s oceans, making algal blooms more common.

Like many of these animals, Cronutt cannot survive in the wild due to his epilepsy, and he was transferred by TMMC in 2018 to Six Flags Discovery Kingdom in Vallejo, Calif., which has facilities to care for wildlife with special veterinary needs.

In recent months, Cronutt’s health has declined due to increasingly frequent and severe seizures. With all other options exhausted, his veterinary team sought help from epilepsy researcher Scott C. Baraban, PhD, in a last-ditch effort to save the sea lion’s life. For over a decade, Baraban, who holds the William K. Bowes Endowed Chair in Neuroscience Research in UCSF’s Department of Neurological Surgery, has been developing the cell-based therapy, which has been shown by his research team to be highly effective in experimental lab animals.

“This method is incredibly reliable in mice, but this is the first time it has been tried in a large mammal as a therapy, so we’ll just have to wait and see,” said Baraban, a member of the UCSF Weill Institute for Neurosciences. “Over the years I’ve come to learn how many marine mammals can’t be released into the wild due to domoic acid poisoning, and it’s our hope is that if this procedure is successful it will open the door to helping many more animals.”

‘A Remarkable Convergence’

On Tuesday, Oct. 6, a team of 18 specialists, including veterinarians from Six Flags and neurosurgeons and researchers from UCSF, successfully completed a precisely targeted injection of brain cell precursors taken from pig embryos — called neural progenitor cells — into Cronutt’s hippocampus, the brain region responsible for seizures. Based on extensive observations in rodents, Baraban said, the injected embryonic cells should migrate through his damaged hippocampus over the course of days and weeks, integrating and repairing the brain circuitry causing his seizures.

Doctors shave Cronutt's head in preparation for surgery. Photo by Shawn Johnson

“It was a remarkable convergence. Every year there are many animals suffering from epilepsy for which there isn’t any treatment available, while, just across the bridge from The Marine Mammal Center, we at UCSF are trying to develop this new form of therapy and looking for ways to one day translate it to the clinic,” said Mariana Casalia, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher who joined Baraban’s lab in 2015 to work on translating the group’s successes in rodents into therapies, and who has taken the helm of the sea lion epilepsy project. “It seemed very natural for us that these animals could be first patients to hopefully benefit from this therapy.”

Domoic acid poisoning in marine mammals causes hippocampal damage very similar to that seen in temporal lobe epilepsy, the most common form of epilepsy in humans. In this disease, damage to hippocampal inhibitory interneurons removes the brakes on electrical activity, leading to seizures. In a vicious cycle, seizures can further damage brain circuitry, which is why epilepsy often worsens over time.

Doctors examine images of Cronutt's brain. Photo by Shawn Johnson

Since 2009, the Baraban lab has been developing a way to replace these damaged interneurons by transplanting embryonic MGE (medial ganglionic eminence) progenitor cells into the hippocampus. As discovered two decades ago by Baraban’s UCSF colleagues Arturo Álvarez-Buylla, PhD, and John Rubenstein, PhD, MGE cells normally migrate into hippocampus during brain development and integrate themselves into the local circuitry as inhibitory neurons.

Baraban’s group has shown that it’s possible to transplant embryonic MGE cells into the brains of adult rodents with temporal lobe epilepsy, where they quickly spread through the hippocampus and repair its damaged circuitry. The procedure reliably reduces seizures in these animals by 90 percent, along with other side effects of epilepsy, such as anxiety and memory problems.

Scott Baraban, PhD. Photo by Elena Zhukova

“Our laboratory’s work has been inspired by the desire to find new solutions for the 30 percent of temporal lobe epilepsy patients who don’t respond to available drug treatments, and for whom no new medicines have emerged over the past 50 years.” Baraban said. “For a number of reasons, including regulatory hurdles, cellular therapies for people with epilepsy are probably still a long way off. However, marine mammals with brain damage from domoic acid poisoning are in a very similar boat — with no effective treatments that would let them ever be returned to the wild.”

Baraban learned about the hundreds of annual domoic acid–related strandings of marine mammals from long-time colleague Paul Buckmaster, DVM, PhD, of Stanford University. Buckmaster’s seminal studies in collaboration with TMMC in Sausalito had found that these animals suffer from hippocampal damage almost identical to human temporal lobe epilepsy.

“As soon as Mariana and I learned about this issue it was clear that our approach could be a perfect solution to help rehabilitate these animals,” Baraban said.

Mariana Casalia, PhD

Casalia had spent four years developing and testing a pig source of MGE cells — pig tissue is often used for transplants into humans — in collaboration with colleagues at UC Davis, work the lab intends to publish soon. On learning about the plight of domoic acid–poisoned sea lions, she partnered with TMMC and the California Academy of Sciences to study sea lion skulls to begin planning an eventual transplant surgery. She ultimately worked with UCSF neurosurgery chair Edward Chang, MD, and collaborators at the medical software firm BrainLab to create a custom targeting system for the sea lion brain. She had even spent months working closely with the Hamilton Company to create a custom needle for delivering the stem cells to the right spot in a sea lion’s hippocampus.

All that remained was to find the right patient. And then, in September, 2020, they got a call from a veterinarian at Six Flags asking if they could help save the life of a sea lion named Cronutt.

Years of Preparation — and a Little Serendipity

After rescuing Cronutt in 2017, TMMC had attempted three times to rehabilitate him and release him back into the wild. Each time he would beach himself again, emaciated, disoriented, and approaching humans. Then he began to have seizures. Most marine centers don’t have facilities for the long-term care of marine mammals with special needs, but Six Flags volunteered to give Cronutt a new home.

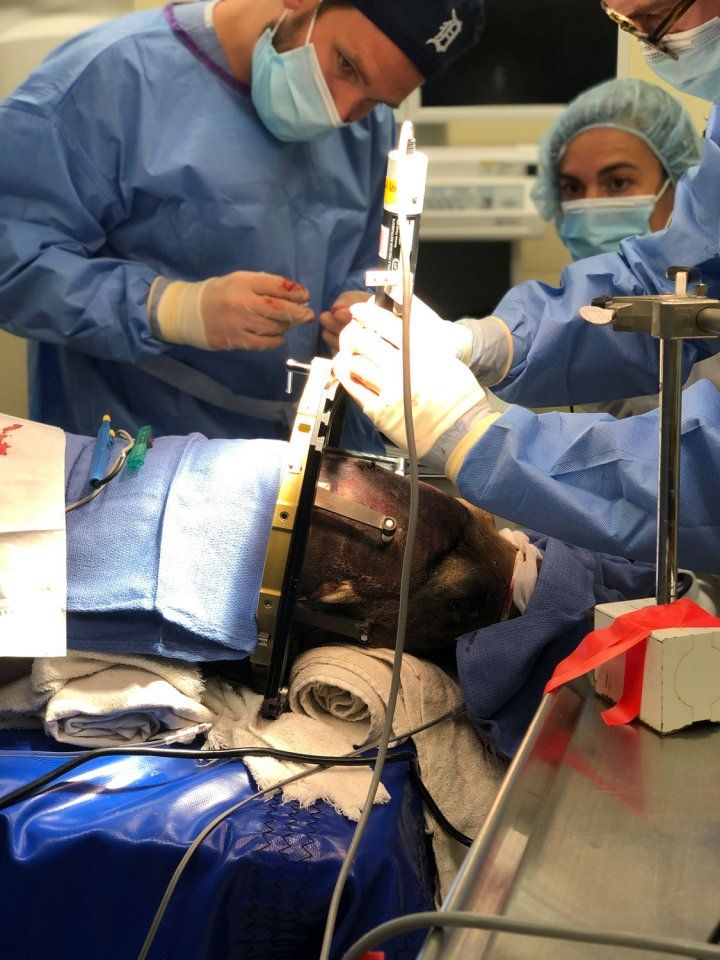

Cronutt receiving cell transplant surgery under the care of Ryan Kochanski, MD, left, Mariana Casalia, PhD, center, and John Andrews, MD. Photo by Claire Simeone

“We have cared for a lot of special needs animals over the years,” said Dianne Cameron, director of animal care at Six Flags. “We adore Cronutt and are committed to providing him a forever home. He has his own ‘apartment’ in our Sea Lion Stadium with a pool and dry resting area. When he’s doing well, he comes out and participates in training sessions. Unfortunately, recently it has been hard to get him to come out of his apartment.”

Over this spring and summer, Cronutt had begun a serious decline — his seizures were increasing, he was losing weight, and he often seemed disoriented. To oversee Cronutt’s care, Six Flags hired Claire Simeone, DVM, a founder and CEO of Sea Change Health, who had studied the neurological effects of domoic acid poisoning during her six years working with TMMC. But it soon became clear that no treatment was working for Cronutt.

“Despite our best efforts and all the tools that we have, his seizures were becoming more prolonged and more frequent over time,” Simeone said. “His brain damage and the effects on his body were getting worse. His decline has been gradual, but we reached a point several months ago where we were questioning what quality of life he had. We had run out of options for how we could successfully manage Cronutt’s disease and knew that we were going to have to make some hard decisions soon.”

Then Simeone recalled a talk Baraban had given at TMMC several years ago about the potential of MGE transplants for marine mammals with domoic acid poisoning. In September, she reached out to ask if the lab might be willing to attempt the procedure as a last-ditch effort to save Cronutt’s life.

Cronutt’s health was slipping fast, but Casalia’s years of preparation for this moment allowed her and her colleagues to quickly assemble everything that would be needed in just one month.

Cronutt the day after his surgery. Photo by Dianne Cameron

In a bit of serendipity that would prove crucial, Cronutt’s brain had already been imaged in 2018 by Ben Inglis, PhD, of UC Berkeley’s Henry H. Wheeler Jr. Brain Imaging Center as part of an ongoing study of how domoic acid poisoning affects the sea lion brain. These MRI images provided critical guideposts that made it possible for UCSF neurosurgeons to plan how they would inject stem cells at just the right spot in Cronutt’s hippocampus.

Cronutt’s surgery, conducted in accordance with COVID-19 protocols at the SAGE Veterinary Centers in Redwood City, Calif., went smoothly, and he was returned to Six Flags. In the days after the surgery his veterinary team reported that he had been sleeping and eating well.

Based on prior experiments transplanting pig MGE cells into rats, the researchers expect it to take about a month or so for the cells to fully integrate into Cronutt’s hippocampus. They will be following up to see if his seizures decrease and his health and behavior improves, and whether his antiseizure medications can be reduced.

“This first-ever attempt has been made possible by funding from a Javits Award from the National Institutes of Health and from the UCSF Program in Breakthrough Biomedical Research. Without these funds, this kind of high-risk, high-reward science would never have gotten off the ground,” Baraban added. “It also depended on Mariana’s fearlessness and perseverance in pursuing this very uncertain project.”

Casalia, who has degrees in applied science and neurobiology from Universidad National de Quilmes and the University of Buenos Aires in Argentina, says the surgery felt like a culmination of everything she’d been working on in her career so far. “I’ve always wanted to apply what we are doing in the lab to the clinical setting,” she said. “For me the ability to do this in reality to help these animals who are suffering is a dream come true.”