NIH Funds UCSF-led Initiative to Chart a Course Toward New Psychiatric Drugs

Psychiatric Cell Mapping Initiative Will Focus First on Autism, Taking Advantage of the Many Genes Implicated in the Disorder

Scientists have struggled for decades to crack the code of psychiatric disorders, but advances in understanding the biology of these conditions have not led to a successful new therapy in 70 years. The drugs that exist for diagnoses like schizophrenia, depression, and autism spectrum disorder (ASD) are blunt, imprecise tools that do not address the full range of symptoms and often do not bring adequate relief.

Scientists have struggled for decades to crack the code of psychiatric disorders, but advances in understanding the biology of these conditions have not led to a successful new therapy in 70 years. The drugs that exist for diagnoses like schizophrenia, depression, and autism spectrum disorder (ASD) are blunt, imprecise tools that do not address the full range of symptoms and often do not bring adequate relief.

But while psychiatric drug research has stagnated, and the pharmaceutical industry has largely abandoned its search for the next Prozac, research on the genetics of these disorders has blossomed.

Now a group of biologists, psychiatrists, and geneticists led by researchers at UC San Francisco and the Gladstone Institutes is leveraging that progress to forge a new path toward novel treatments for these conditions.

Armed with an $18 million grant awarded by the National Institutes of Health on Sept. 5, 2018, the researchers are launching the Psychiatric Cell Map Initiative (PCMI), a collaborative effort to chart how gene mutations lead to psychiatric disorders in the hopes of identifying new drug targets that could prevent, treat, or even cure these conditions.

The PCMI was founded by the UCSF Quantitative Biosciences Institute (QBI) in collaboration with the Department of Psychiatry. Founding faculty include QBI Director Nevan Krogan, PhD, a professor of Cellular and Molecular Pharmacology at UCSF and a Gladstone senior investigator; Matthew State, MD, PhD, the Oberndorf Family Distinguished Professor and chair of Psychiatry at UCSF; and Jeremy Willsey, PhD, an assistant professor in the Department of Psychiatry and the Institute for Neurodegenerative Diseases at UCSF.

That arc, from gene discovery to drug development, has never happened in psychiatry before as it has in cancer or cardiovascular disease.

Chair of UCSF Department of Psychiatry

“There's been a profound transformation in our knowledge of genetic risk for psychiatric disorders over the last decade, particularly with neurodevelopmental disorders. That progress has opened the door to understanding the pathophysiology of these conditions in an unprecedented way,” said State who is also the director of the Langley Porter Psychiatric Institute and a member of the UCSF Weill Institute for Neurosciences.

“The challenge moving forward is to take a large and functionally diverse group of genes and figure out how they lead to the development of disease. And then, most importantly, to translate that into the development of novel treatments,” State added. “That arc, from gene discovery to drug development, has never happened in psychiatry before as it has in cancer or cardiovascular disease.”

The new initiative – outlined in a Perspective article published in Cell on July 26, 2018 – involves a diverse set of collaborators from across UCSF, Gladstone, and the University of California system, including computational biologist Trey Ideker, PhD, of UC San Diego; and CRISPR pioneer Jennifer Doudna, PhD, of UC Berkeley, who recently opened a new lab at Gladstone to pursue biomedical applications of genome editing. Doudna is also an adjunct professor of cellular and molecular pharmacology at UCSF and executive director of the joint UC Berkeley–UCSF Innovative Genomics Institute.

Translating Genes into Drug Targets

Over the last 10 years, scientists at UCSF and elsewhere have excelled at identifying genes that contribute to psychiatric disorders. But so far these long lists of genes have not given researchers the clues they need to solve the puzzle of these conditions.

“The hope was that once we’d identified genes associated with a particular disorder, we could look at what we know about the functional roles of those genes and it would be obvious what was causing that disorder. But that’s turned out not to be the case for the vast majority of conditions,” said Willsey, who is also a member of the UCSF Weill Institute for Neurosciences.

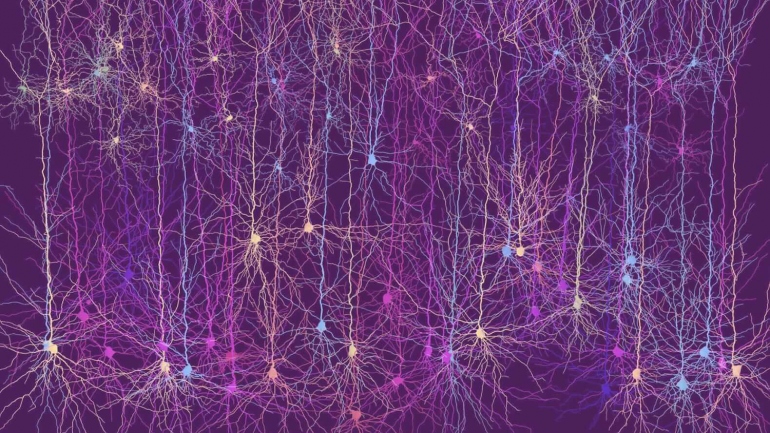

So PCMI is trying a new tactic. The researchers are focusing on the proteins that are encoded by the genes implicated in neuropsychiatric disorders. Proteins are the functional output of genes and are the workhorse of the human cell. In some cases, one protein can impact the expression of many genes by altering chromatin, the “packaging” of the genome. Other proteins may interact with one another to contribute to cellular processes like neuron development. By understanding the proteins, the researchers hope to better understand the genes – and the disorder.

The first step will be to map the interactions of each protein, building a network of physically and functionally connected proteins. With this knowledge, the researchers hope to discover key points of overlap. For example, mutations in 10 different genes may affect 10 different proteins, but those 10 proteins could all be part of the same functional pathway. Suddenly, 10 genes are narrowed down to one function and, ideally, one drug target.

“Making these maps and looking at the protein networks across development is a very powerful way to make sense of these sets of gene mutations. Suddenly, you go from 65 genes to five pathways, and that makes it much more interpretable,” Krogan said.

The researchers will also assess the real-time impact various gene mutations have on the development and function of brain cells. To do this, they will add the mutations to stem cells using CRISPR genome editing, develop the stem cells into different types of neurons, and see how the cells respond. Eventually, they plan to repeat the process in 3-D models of human brain development derived from stem cells and in frogs to understand how the mutations affect the development and function of the brain as a whole.

Rather than prioritize any one gene first, the researchers are taking a hypothesis-free approach, testing all the genes simultaneously and not assigning them a function prematurely. “Instead of having preconceived notions about what the genes are doing and how that might be related to disease, we’re going to take a step back and let basic biological principles show us how to find promising leads,” said State. “Testing the genes simultaneously is not just about being thorough. It’s about the underlying strategy of looking for convergence and letting the biology reveal itself through unbiased methodologies.”

Achilles’ Heel of the Cell

PCMI will first tackle autism spectrum disorder (ASD), one of the best genetically-characterized disorders, with 65 genes identified. The researchers also plan to apply their method to Tourette disorder, childhood-onset epilepsy and intellectual disability in the near future.

Cell Mapping Initiatives

UCSF’s Quantitative Biosciences Institute has collaborated to launch three initiatives.

In addition to helping them understand each disorder on its own, the scientists believe the cell maps will reveal overlapping proteins and pathways shared among the different diagnoses. Already, they have identified mutations in the same genes for different psychiatric disorders. And their ambitions are not limited to the brain. Building on similar initiatives started by Krogan’s team at QBI, including the Cancer Cell Map Initiative (CCMI) and the Host Pathogen Map Initiative (HPMI), the researchers think many of the pathways and proteins that are dysfunctional in neuropsychiatric disorders will also be implicated in seemingly unrelated conditions, such as cancer and even infectious diseases. Indeed, it is well-established that an overlap exists between genes involved in neurodevelopmental disorders and in congenital heart disease.

“The same genes being mutated in autism are being mutated in heart disease, and the same genes being mutated in cancer are being hijacked by HIV. There’s a common set of pathways that are arising,” said Krogan. “These vulnerable pathways are the Achilles’ heel of the cell, and they’re our best target to treat or prevent disease.”

In addition to Krogan, State and Willsey, PCMI principal investigators include David Agard, PhD, of the UCSF Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics; Martin Kampmann, PhD, and Michael Keiser, PhD, of the UCSF Institute for Neurodegenerative Diseases; Tomasz Nowakowski, PhD, of the UCSF Department of Anatomy; Brian Shoichet, PhD, of the UCSF Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry; Mark von Zastrow, MD, PhD, of the UCSF departments of Psychiatry and Pharmaceutical Chemistry; Steven Finkbeiner, MD, PhD, a Gladstone investigator and UCSF professor of pharmaceutical chemistry; Trey Ideker, PhD, of UC San Diego; and Jennifer Doudna, PhD, of UC Berkeley, Gladstone, and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.