The Breath of Life

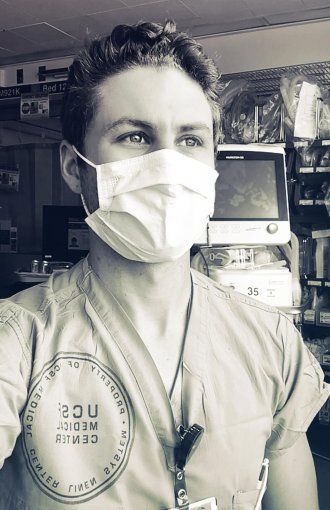

With COVID-19, respiratory therapists such as Max Rausch must reinvent their practice with each patient.

Max Rausch, captured via FaceTime in an ICU at UCSF’s medical center on Parnassus on May 16 at 1:30 p.m. by photographer Steve Babuljak

COVID-19’s aggressive attack on the lungs has brought the role of respiratory therapists (RTs) into the public eye. Max Rausch specializes in critical care respiratory therapy and works in the medical and surgical intensive care units on the Parnassus campus.

Rausch works up to six 12-hours shifts, then goes home to Bend, Oregon, for two weeks, where his girlfriend is an ICU nurse. “I love Oregon and I love UCSF. Thankfully, I didn’t have to choose,” he says. When the lockdowns began, he switched from flying to making the seven-hour road trip. “It’s a nice drive,” he says. “I don’t mind it.”

What’s your baseline work, prepandemic?

Someone ends up on a ventilator because they’re not able to breathe for themselves, so we have to help them breathe. We can get the oxygen in and carbon dioxide out in various ways – we’ve got a hundred different knobs and buttons we can push and fine-tune.

An RT and a doctor intubate a patient together – put in the breathing tube – and then I connect the tube to the ventilator and find optimal settings for the patient. We also do techniques to expand the lungs and clear secretions; we monitor airways and administer oxygen therapies and inhaled medications.

Has your ICU been crowded with COVID patients?

The biggest surge I saw was when about half of my ICU was COVID-positive and on a ventilator, so roughly seven or eight patients. But we haven’t really seen a true surge, luckily. What was tough was when I had four ventilated patients, and two of them were having problems at the same time. Getting protective gear on quickly and running into another isolation room is hard.

What’s most challenging about treating these patients?

There are some general settings and strategies that work for many patients on ventilators – like turning people on their stomachs to help improve the oxygenation of their blood. But a lot of COVID patients aren’t responding to that technique. And the disease attacks each individual differently, so we’re having to get inventive and figure out what works and doesn’t work.

Many COVID patients are following the same course, where one minute they’re on just a little oxygen and then in the blink of an eye they’re on a ventilator.”

Many COVID patients are following the same course, where one minute they’re on just a little oxygen and then in the blink of an eye they’re on a ventilator. They’re up, on their phone, talking to their wife – they look fantastic. But their oxygen starts dropping out of nowhere, and we’re turning it up and it’s still dropping. Subjectively, they’re doing fine. And we have to say, “I know you feel fine, but we have to put you on a ventilator right now.” People may manifest those lower oxygen levels in different ways. They might not feel like “I can’t breathe,” but they might be in danger. So I’ve learned to really assess the patient more closely and not just look at the numbers.

What has that been like – having so little knowledge about this new disease?

When I first started getting COVID patients, I was excited to be on the front lines of something so dramatic. But I soon realized how difficult treating these patients was going to be. I would often get home from work and spend the evening talking with my girlfriend on FaceTime about the challenges we both faced that day. I couldn’t sleep. Many times I would find myself wide awake, thinking about new ventilator strategies I could try the next day.

To do your job, you’ve got to be right there next to the sickest patients. Is that worrisome?

I was nervous for a little while, but once a patient is on a ventilator, their every breath is contained in a closed circuit. There is risk; if the circuit were to become disconnected, their viral load could potentially be aerosolized. But if everything stays nice and enclosed, it’s safer than having a patient not on a ventilator, coughing.

But everyone’s being cautious. We have what we’re calling “the PPE police.” It’s essentially just different nurses going around making sure everyone’s keeping a close eye on their hand-washing, mask usage, things like that. Just reminding you, like, “You should wash your hands a little bit longer” or “How long have you had that mask?”

What keeps your spirits up?

I’ve had lots of patients who were extremely sick, and they made it home. In the ICU, I get to work with a patient for up to five days in a row, which gives me a lot of time getting to know them and figuring out what's going on. It’s seeing people on their deathbeds, people who are nearly gone, and trying to get them better.

More from this Series

Between shifts at San Francisco’s public hospital, physician and podcast host Emily Silverman, MD, collects audio diaries from health workers across the nation.